Networked Urbanism

design thinking initiatives for a better urban life

apps awareness bahrain bike climate culture Death design digital donations economy education energy extreme Extreme climate funerals georeference GSD Harvard interaction Krystelle mapping market middle east mobility Network networkedurbanism nurra nurraempathy placemaking Public public space resources Responsivedesign social social market Space time time management ucjc visitor void waste water Ziyi

social

Focusing on the relationships between people in a given context. Our role as designers being to connect our design and strategies with people’s needs and initiatives, to assist the creation of communities and to enable systems and spaces for interaction, social creativity, and the emergence of behaviors.

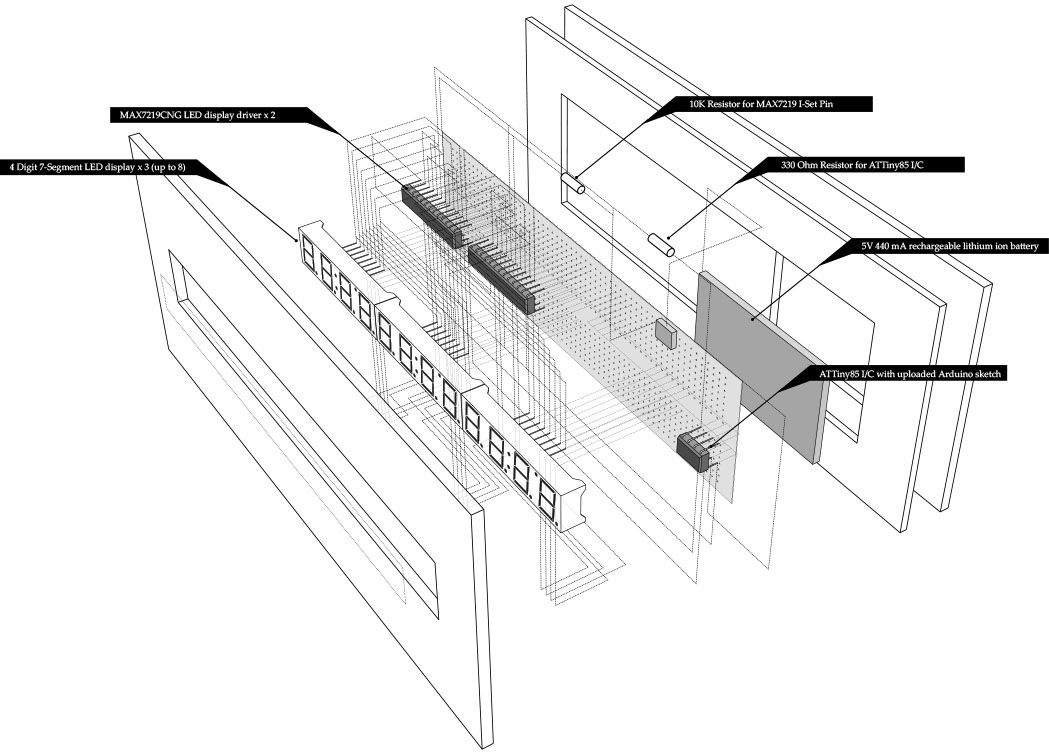

The carbon counters (in both physical and digital form) are meant to stimulate discussion about carbon emissions and climate change at the school of design. The impact that our buildings have on the environment is an issue that is often glossed over at the school of design as it is in most public discussions. If we want to address our concerns for the environment, issues of climate change need to be brought into our collective consciousness and that starts with raising awareness about own carbon footprint.

Climate change is an issue of global concern, with deep roots connected to everything from aging infrastructures to shortsighted policies and regulations. However climate change is also largely the result of behaviors caused by a lack of awareness about the impact our actions have on the environment. Every time we use our computers, turn on the air conditioning, or take a shower, we are releasing carbon into the atmosphere and contributing (in a small but nonetheless significant way) to global climate change. As a result of this general unawareness, people leave their lights on during the day, turn the air conditioning on high in the summer, and take hot showers longer than necessary – exacerbating the problem of global warming.

This semester began with an assumption that educating the public about the way our built environment works, specifically the way our built environment uses energy and contributes to the problem of global warming, has the potential to correct some of our more problematic behaviors. One component of education is finding ways to visualize the invisible yet ubiquitous energy infrastructure and how that infrastructure operates. The other is to visualize the real-time impact our buildings have on the environment, and in so doing affect the decisions we make regarding how we interact with the built world.

While there are undoubtedly many ways to communicate this information, the studio was an opportunity to experiment with an unfamiliar medium: animation. The first experiment involved an animation describing the movement of energy from the point of resource extraction to the point of consumption (the city of Boston). Since Boston, like many northeastern cities, creates most of its useable energy from burning natural gas, the animation begins in the Mississippi Delta where most of the nation’s natural gas is processed before it travels via one of several large pipelines to the electric generation facility. The fact that Boston relies heavily on natural gas for its electric generation is an important point because it enables one to calculate the amount of carbon created per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated.

This first animation was an introduction to new tools, and new techniques of representation. While it was an informative exercise, it failed to communicate the urgency of reducing our collective energy footprint. The description of resource movement from source to sink was ultimately too abstract and removed from the everyday behaviors of ordinary citizens. Using the lessons learned from this first iteration, the second animation used data collected from actual buildings to concretize what was formerly too abstract.

Even with the complexities involved in the processes of energy generation and transmission (deregulated markets, interconnected power grids…etc.) collecting and animating information about how specific buildings or groups of individuals use energy is decidedly more difficult. In order to streamline the research, Gund Hall served as a test kitchen because of their psuedo open data portal to energy monitoring systems. Real-time data on everything from lighting loads to steam use is continuously collected, packaged, and then emailed as a text file once per day. Using this information, the numbers in the animation are presented in traditional terms, such as a Kilowatt-Hours for electricity used for lighting and therms for heating, as well as comparative figures such as number of houses powered per year. For example, the amount of energy used to light Gund Hall is equal to the amount of energy it would take to power 208 medium sized houses. The numbers and figures are also presented in relation to other buildings on the Harvard campus as a way to accentuate the point that Gund uses more energy per square foot than almost any other building in the area except the Science Center (and most of this energy goes toward unnecessarily lighting the building during all hours of the day).

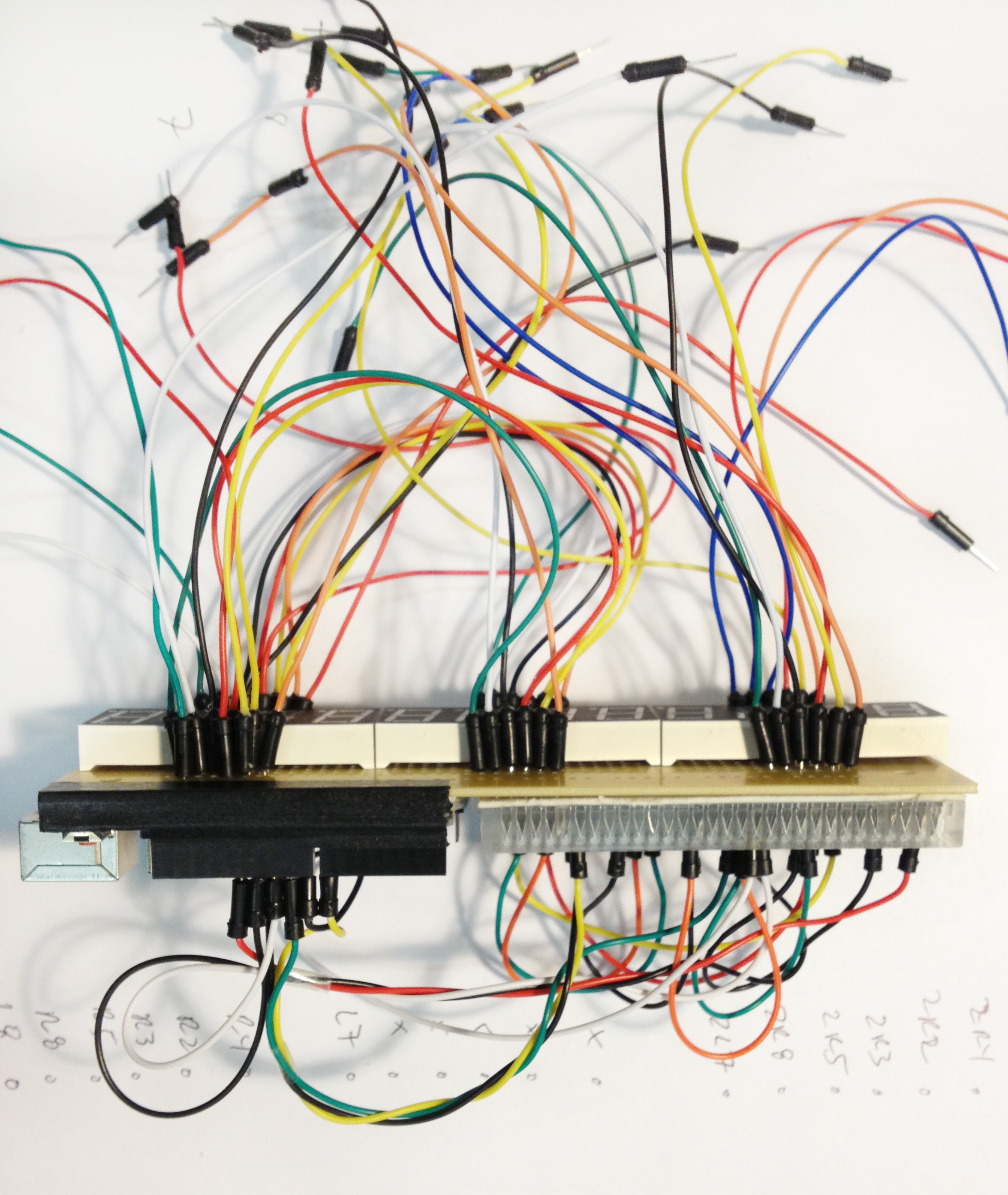

This animation played in the Chauhaus alongside a device that reads the (almost) real-time carbon emissions of Gund Hall. Although the output from this carbon counter is a simple number, the device was designed as an object of intrigue that people could walk up to and investigate – a dynamic and slightly more interactive type of informative poster.

These types of displays are particularly important for the design school, since we as designers are rarely confronted with the reality of how our creations impact the environment. Buildings account for almost half of all carbon emissions in the United States, and designers have a responsibility to create an efficient and responsible built environment. If an awareness of energy use becomes part of our consciousness as designers, and if we are constantly reminded of the ways in which our creations use energy, we are more likely to design and create a better built environment for the future.

FunChinese is a project aiming to connecting people with complementary language skills to share with each other. Through the physical interaction, people begin to gain not only languages but also the knowledge of another culture. More importantly, participants get a natural familiarity with a group of people rather than a single one. And further, this will bring a sense of involvement in the larger community, and more open to new things that one encounters as a new-comer.

Boston has become more and more international. In particular, from 2000 to 2010, the Asian population in Boston multiplied by 1.6. Not only do they represent a minority group of people but also they bring different cultural backgrounds.

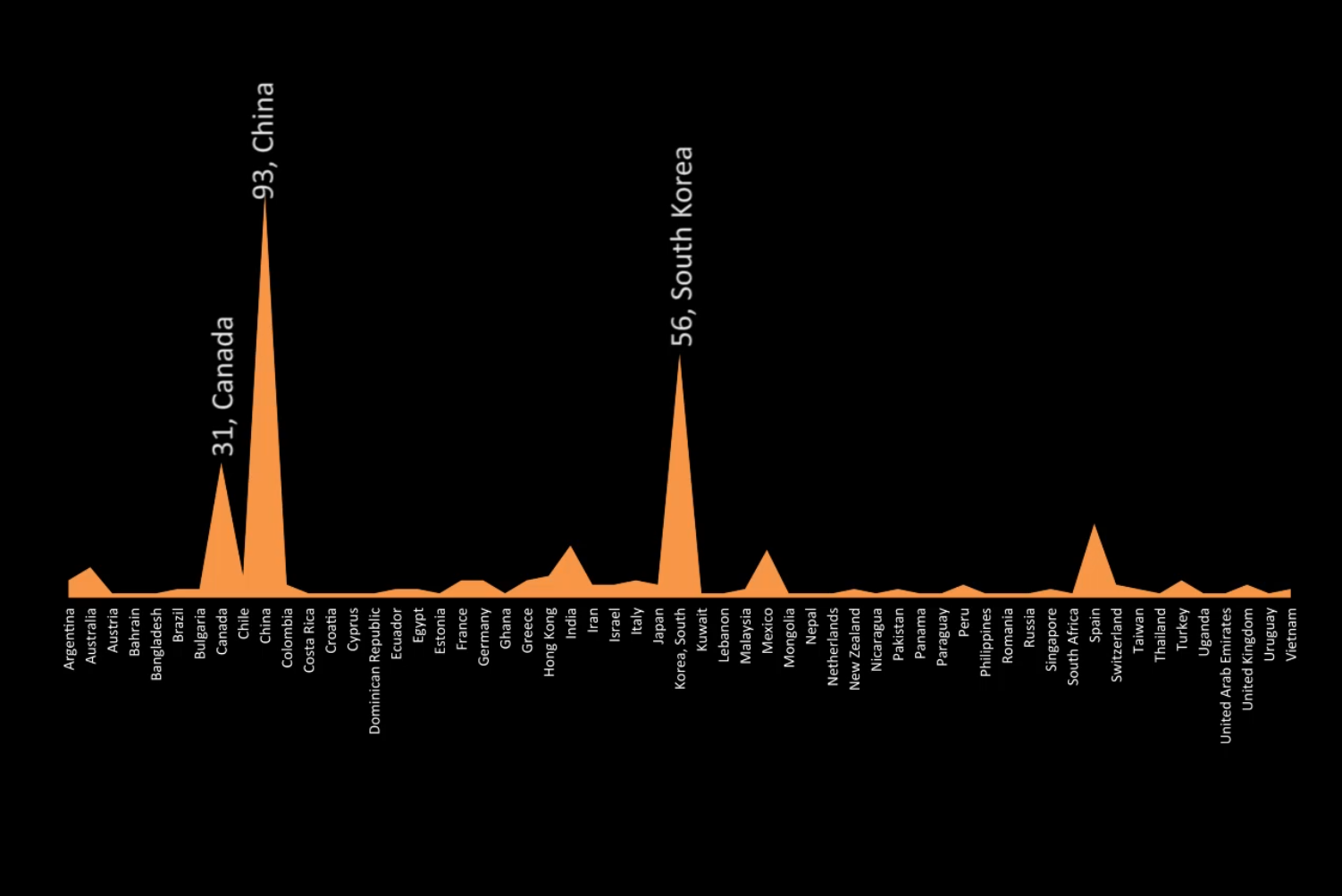

Among the growing Asian population in Boston, international students represent an important group. In the Graduate School of Design, there are 327 international students from 56 origins, which accounts for 39.8% of the 821 students. Among these students, more than 150 are from Asia, mainly China and South Korea. Since the cultural background and mindset of Asian students are fundamentally different from the western world, it is hard for them to adapt into the life in the US.

Some Asian students felt reluctant to speak or make friends. Not because they don’t have the ability to communicate, but because of a natural insecurity in a new environment. On the other hand, international students tend to stick much more to people from the same country.

As the number of international students continues to grow in the GSD and at the larger Boston area, it becomes important to help them better and faster adapt to the new environment. This will benefit international students, and also bring a more healthy and active interaction between all students.

FunChinese takes language as a tool to connect people from distinct backgrounds. Language influences the way different people see the world. It is also a door through which we begin to understand the core of a culture, its ideology as well as deeper meaning. Through the sharing of one’s own culture, students become more open to communicate with peers and thus building a more healthy connection.

International students come from a different culture and are able to bring a diverse insight in a discussion. Especially students from countries like China, South Korea, where there are many developments happening, this cross-cultural interaction could lead to professional practices.

Taking Chinese as starting point, FunChinese takes action by involving students with a Chinese background with students who have interest in Chinese language or Chinese culture, through the form of group meeting and one-on-one interaction. The project starts in the small community of GSD, and then grows in collaboration with the School of Engineering. In the whole process, this project has received highly positive support and response from participants and school directors, and is aiming to continue and expand in the next year.

By contributing to the community, members have benefited from a cross-cultural exchange. Through the weekly interaction, American participants have got the chance to know more about Chinese culture; Chinese participants have been able to engage themselves with the larger GSD community, and found a self-identity as a valuable member with a distinct and meaning cultural background.

FunChinese takes Chinese as a prototype of promoting cultural communication through the means of language.

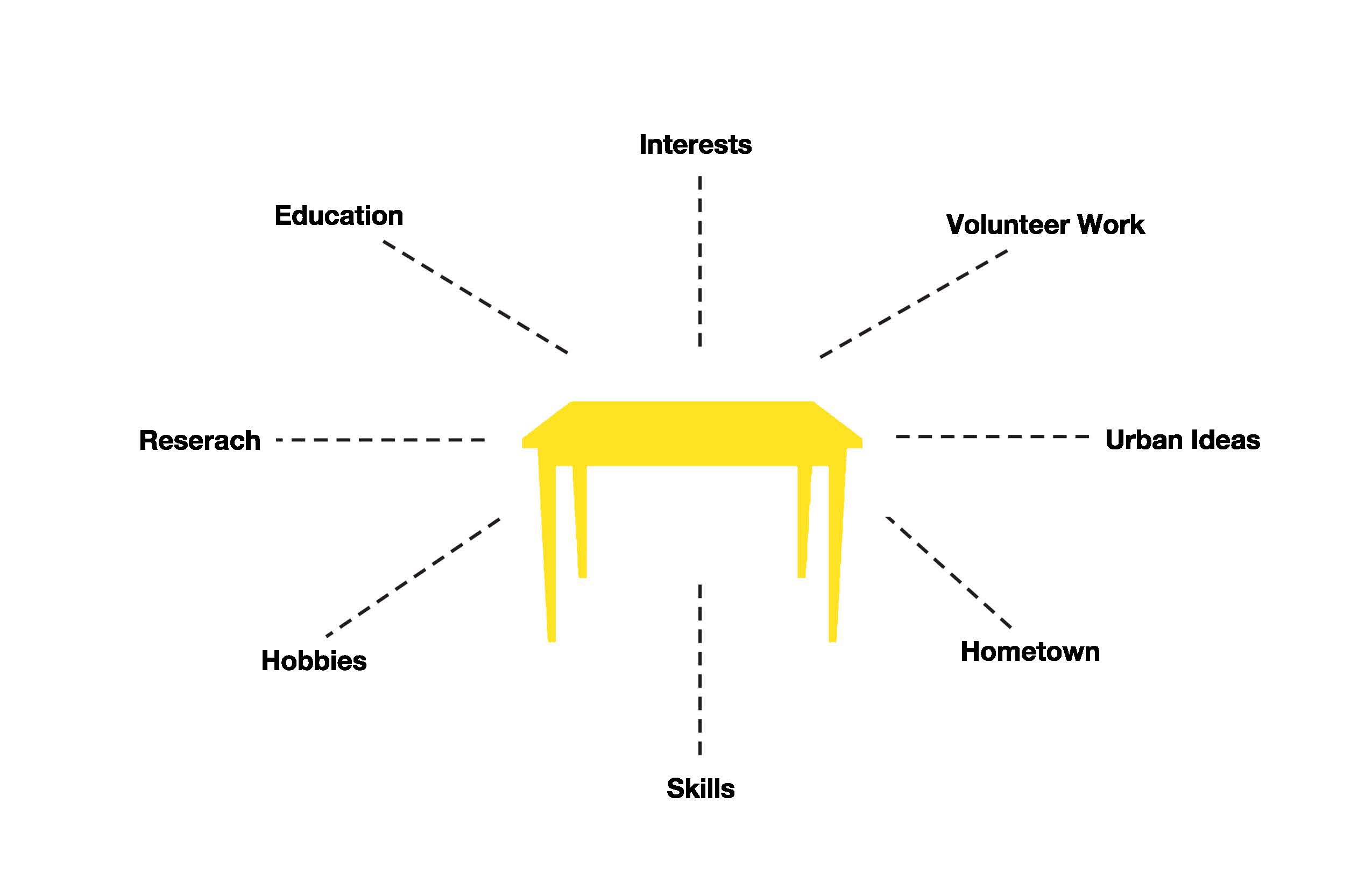

Table Talk is a physical social network connecting individuals of like interests by combining the physical and digital realms of urban space. This new community typology makes formerly invisible layers of shared interest visible in the material space. By embedding personal metadata onto physical objects, a new community work space is developed connecting individuals in both real time and to past occupants; highlighting the importance of the city as place.

Looking at the history of social networking, social connections first and foremost were always spatial. With the invention of the internet, social interaction went from physical to digital and new geo-location technology begins to bring the physical back into social networking, yet only as a dot on a map. What if instead of separating our physical and virtual layers, there was a way our physical environment could become a social network?

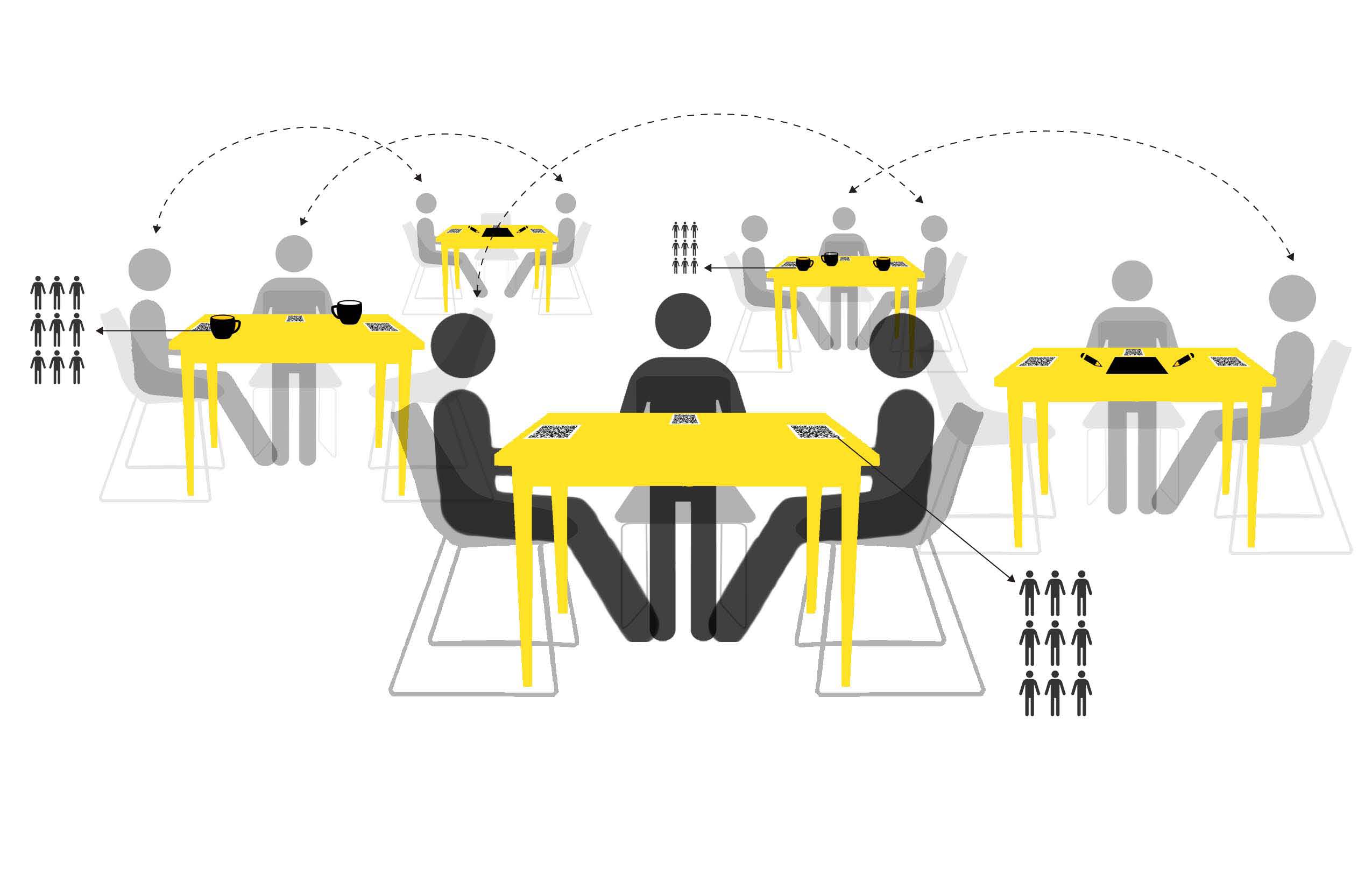

TableTalk is the exploration of the static object with an overlaid layer of digital technology which allows the user to embed personal metadata. Each table is networked into a larger system within the room. As an individual ‘engraves’ their interests onto the table; the system is able to delineate shared layers between occupants, connecting people in real time. Once the table receives an individual’s interests, it retains a trace of that person so that connections can occur across temporalities. Based on chance occurrence of choosing the same table, individuals of shared interests can connect through the physical environment. People can leave traces of themselves on the table for the past and the future; adding a heightened importance to place.

With the increased use of the ‘in between’ place between work and home where individuals come to work independently in public, TableTalk further enhances the social quality of this space. This new typology is a place to work alongside other intellectuals, some of which may share an inherent knowledge base, and connect on mutually beneficial terms. This type of environment not only provides a work space, but starts to break social barriers through place, creating a richer way for people to connect, develop community, provide place for organizing and therefore become a tool for place making.

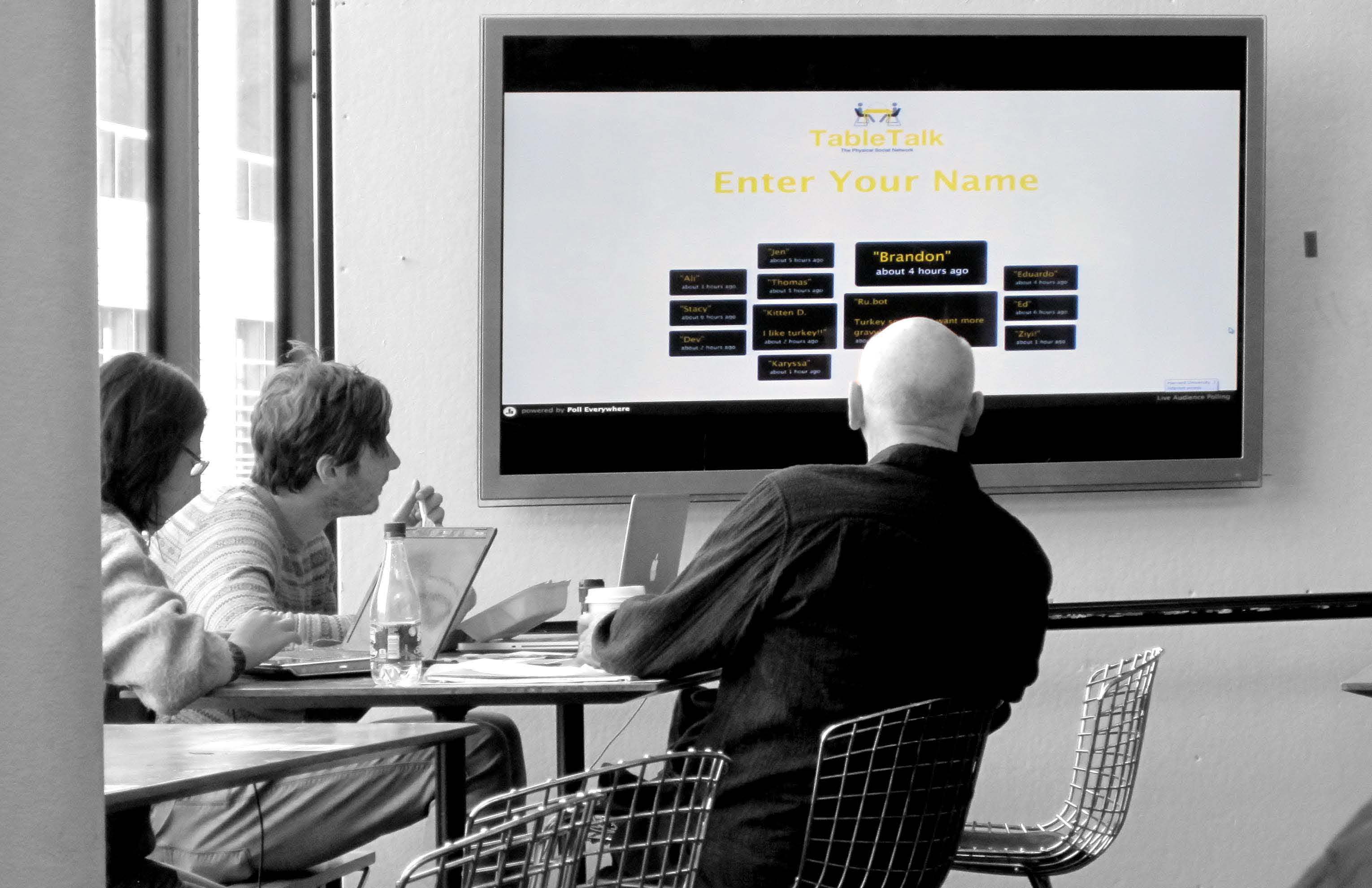

There are several approaches to implementing this physical social network; each incorporating a different level of technology; the first being the simplest means as an overlay onto an existing space. Using QR code stickers, a physical space can be advanced by simply overlaying a digital layer onto its existing surface. The individual can then scan the QR code using their phone and input their layers of interest to begin to connect with others in that space. The first implementation of TableTalk was an overlay in the cafeteria of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. When a user scanned one of two QR codes on the table, they were prompted to choose one of four topics which brought them to an online message board to reply to past users or leave notes for future. The second QR code let the user leave a visible trace of themselves in the room. When this code was scanned, the user was prompted to enter his or her name which was then immediately displayed on a large plasma screen in the cafeteria. My initial hypothesis was that users would be more willing to use the less visible online message board rather than display their names in public; however I was surprised by the inverse results. More users publicly displayed their name rather than using the online message board. Many went on to further add comments and the screen became a show many would stop to watch. After a few days use, I discovered more messages were added to the online board; most of those in the topic ‘food & drink’; not so surprisingly being in a cafeteria. However, it makes me wonder that if this technology were located in a place without a specific program as this cafeteria had, would TableTalk be able to influence the program of a non-programmed space?

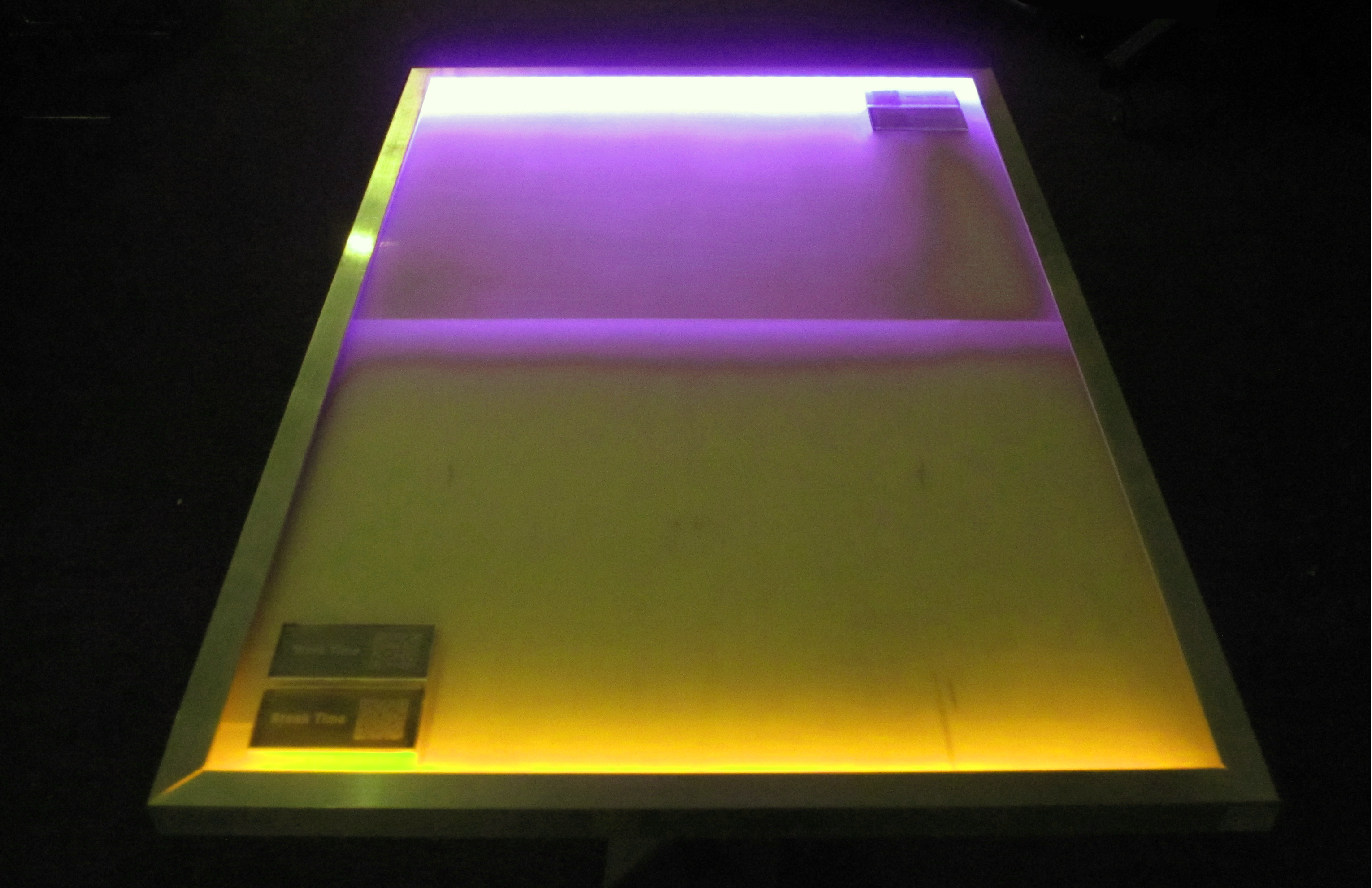

In a fully immersed environment, the technology would be integrated into the table itself; fully combining the digital and physical layers. For this, I designed a responsive table which is capable of absorbing user interest. Depending on the chosen topic, the table adjusts color so that the user is able to quickly look around the room and see others currently in the room with similar interests; breaking that barrier of first conversation starter. The table is also embedded with a QR code which when scanned, connects to all the others who had previously chosen that same seat with the same interest.

By infiltrating unused spaces of our communities with these responsive tables in a layout that promotes social interaction, that ‘in between’ space can begin to act as a place making tool and means for community engagement. This physical social network can begin to connect individuals within the community on deeper and more meaningful levels depending on hobbies, background, research, or need and therefore highlighting the importance of city as place.

Boston has become more and more international. In particular, from 2000 to 2010, the Asian population multiplied by 1.6. Not only do they represent a minority group of people but also they bring different cultural backgrounds.

Taking Chinese as starting point, FunChinese is a project aiming to connecting people with complementary language skills to share with each other. Through the physical interaction, people begin to gain not only languages but also the knowledge of another culture. This is a prototype of promoting cross-cultural exchanging.

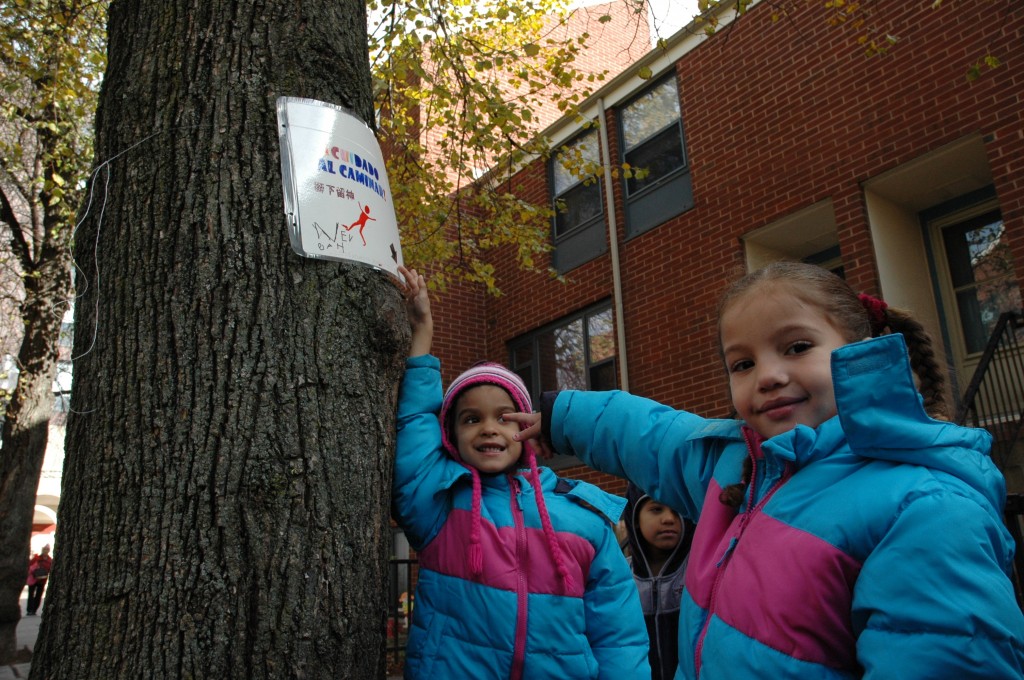

During November, I have led a series of urban planning workshops with different programs of IBA (Villa Victoria). The workshops became platforms for residents to see the community through a new perspective in which they can map problems and propose solutions for future developments. Given the time constraint only one of the workshops has been taken to a design stage. The students of Escuelita Boriken hand-painted street signs in which they alert residents of bumps and cracks on sidewalks of their community. The event granted 5 year-old students the unique opportunity to act on their built environment and transform it in a positive way.

The biggest challenge to reducing our collective energy footprint is visualizing what is normally unseen and forgotten, namely the energy we use everyday. Of course, even if our energy use is rendered as a number, or a graphic, it’s a bit too abstract to actually change our behavior. My initial experiments with this idea led to the development of the carbon counter that is currently displaying the carbon output of the GSD in the Chauhaus. The idea was that people would come up to this object of intrigue, snap a picture of the QR code, and be led to the Architecture 2030 Challenge website (which challenges architects and urban designers to realize net zero projects by t he year 2030). Not surprisingly, this device is pretty hard to miss, so I’m currently trying to think of an installation that will attract more attention to the actual flows of energy at the GSD. The installation is going to be coupled with a brief animation that describes all the ways that the GSD is using energy, and how to improve our collective performance.

Currently, I’m working on the back end of the system to get energy information in real time from individual plug loads. I received a plug monitor that runs the open-source protocol Zigbee that will interface with an Xbee adapter that I already have hooked up to an Arduino. The challenge now is to make the two devices communicate with each other, and then design a system that will turn this information into a visual and physical spectacle.

Bostonians, through their water usage, are one part of an extensive, connected system. The delivery of water to and from your home comprises of more resources than water alone and results in large scale infrastructural interventions that shape our landscape and impacts ecosystems on both sides of the chain. Through exploring methods of communicating these concepts, I hope provide a tool that educates users, encouraging them to reduce water usage and a have a better awareness of their environmental impacts.

Hear Here! is a platform that allows you to engage in virtual discussions with people within your vicinity. You can target an audience based on their location (be it your neighbors, concert goers, park patrons, building occupants, etc.) and engage in a rich exchange of information (ie. discussions, photo sharing, classifieds, comments, announcements, etc.). Hear Here aims to strengthen community by facilitating communication amongst other locals.

Most recently, my efforts have been focused on mobilizing existing talents and resources in the Cambridge and Harvard communities to activate urban spaces in new ways. My studio project has culminated in a community arts event to connect the Cambridge and Harvard communities through art, dance, and food. The event is called Decemberfest, and it will take place on Saturday, Dec. 1, from 3-5pm at the GSD in Rooms 121-123. The project is supported by the Harvard Urban Planning Organization, and it will feature performances by dance groups from the Harvard and Cambridge communities, as well as art from local residents on an urban theme. The entire community is invited to this public event – hope to see you there!

TableTalk is a physical social network connecting individuals of like interests by combining the physical and digital realms of urban space. This new community typology makes formerly invisible layers of shared interest visible in material space. By embedding personal metadata onto physical objects, a new community work space is developed connecting individuals in both real time and to past occupants; highlighting the importance of the city as place.

I am currently exploring the many ways this system can be implemented; including overlay onto existing program, embedding into objects, enhancing the social environment, and designing a new typology all together.

« Previous 1 … 4 5 6 7 8 … 10 Next »