Networked Urbanism

design thinking initiatives for a better urban life

apps awareness bahrain bike climate culture Death design digital donations economy education energy extreme Extreme climate funerals georeference GSD Harvard interaction Krystelle mapping market middle east mobility Network networkedurbanism nurra nurraempathy placemaking Public public space resources Responsivedesign social social market Space time time management ucjc visitor void waste water Ziyi

awareness

Making people more conscious about the processes and issues that affect the city and the territory. Enabling channels for transparency and open data, starting actions and campaigns that make important topics visible, monitoring the reality to make it easier to understand its behavior.

I hope early summer is finding you all well. I am on my short break between Spring and Summer term, so I thought I’d give you an update on the Bird’s Striking Building project.

Since March, I have been working with the City of Portland’s Bureau of Sustainability who had created the Bird Friendly Design Guide. They are currently creating a policy that will require bird-friendly design in any new or remodeled city/government projects that are in high-risk zones for bird strikes. They used the video as part of the process of creating their legislation (and were very thankful and complementary!) and they have also had me help them review the actual written legislation/code.

The American Bird Conservancy has also contacted us and wants to use our video for the lobbying they do in Washington DC. Since the video was Portland based, we are talking about altering it for a general audience. Currently, Liz and I are in talks with their marketing coordinator about this. They may end up hiring a professional crew – IE – they have a real budget for actors – their last video had Richard Chamberlain as the narrator. Even if that happens, Liz and I will be involved and they will credit both of us (and PSU).

Recently, I’ve been talking with Portland State University’s Sustainability Office as they are now internally discussing the issue. They are considering working on the windows at the Rec Center and the University President’s office. The Rec Center is the location that Liz and I tried to film the bird ghost but were run off because we couldn’t get permission to film in time.

The Portland Audubon has posted our video at http://audubonportland.org/issues/metro/bsafe/birdsafe

Also, Ornilux, the “spider web” glass manufacturer has posted the video on their website http://www.ornilux.com/bird-

Well, I’m now going to be spending the summer deciding on my thesis topic for this next year. The bird’s are definitely on my mind, but I am also considering other city-animal habitat interactions. My contacts at the Audubon and the City of Portland’s Bureau of Sustainability will be people I will get in touch with to discuss thesis ideas. The Networked Urbanism project has given me the opportunity and contacts that will take me forward in my career.

Thank you! ;-)

Karina

We have created page accounts to go along with our app. This allows for deeper connection and to get the ball rolling on creating this app as a marketable item. Also along with the use of Facebook and Twitter as base pages, we have created a hashtag that goes along with our app and pages to further group conversations and connections.

https://www.facebook.com/bikingportland

https://twitter.com/BikingPDX

#bportland

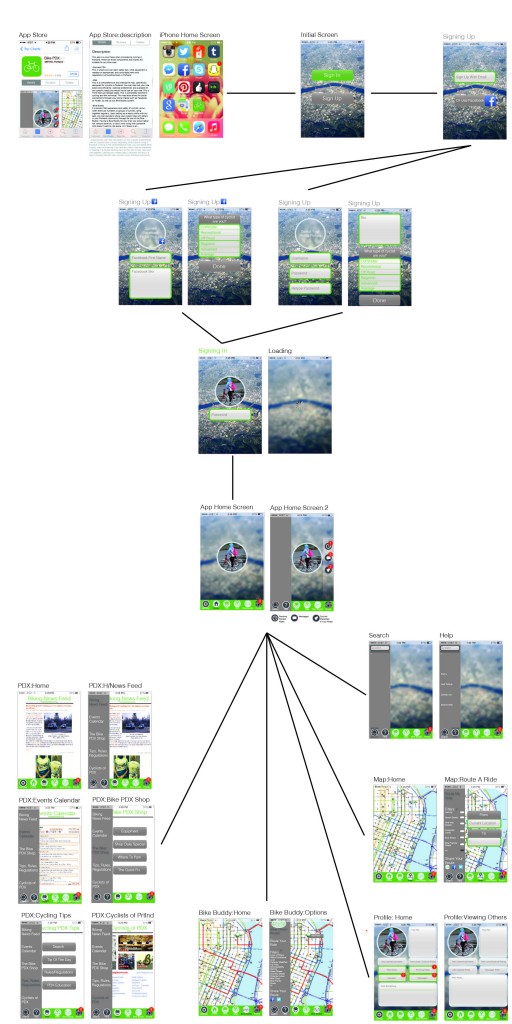

Here is a mapped out version of the development of the Bike PDX app so far…

A few independent groups in Massachusetts are trying to encourage a more positive acceptance of our mortality and how we think of and plan for death. Among them are the Green Burial Committee ( a sub-committee of the Funeral Consumer’s Alliance of Massachusetts) and Mourning Dove Studio. The documentary series Earthrise recently interviewed the two groups and their video, “Green Goodbyes,” takes us on a short tour of the limited green burial network in the state…

You can also check out my own interview with Ruth Faas in the post “Mourning Dove Studios” (coming soon).

Bostonians, through their water usage, are one part of an extensive, connected system. The delivery of water to and from your home comprises of more resources than water alone and results in large scale infrastructural interventions that shape our landscape and impacts ecosystems on both sides of the chain. Through exploring methods of communicating these concepts, I hope provide a tool that educates users as to what resources go into the treatment and transport of water, how they’re using water in their homes and why it’s important to conserve it.

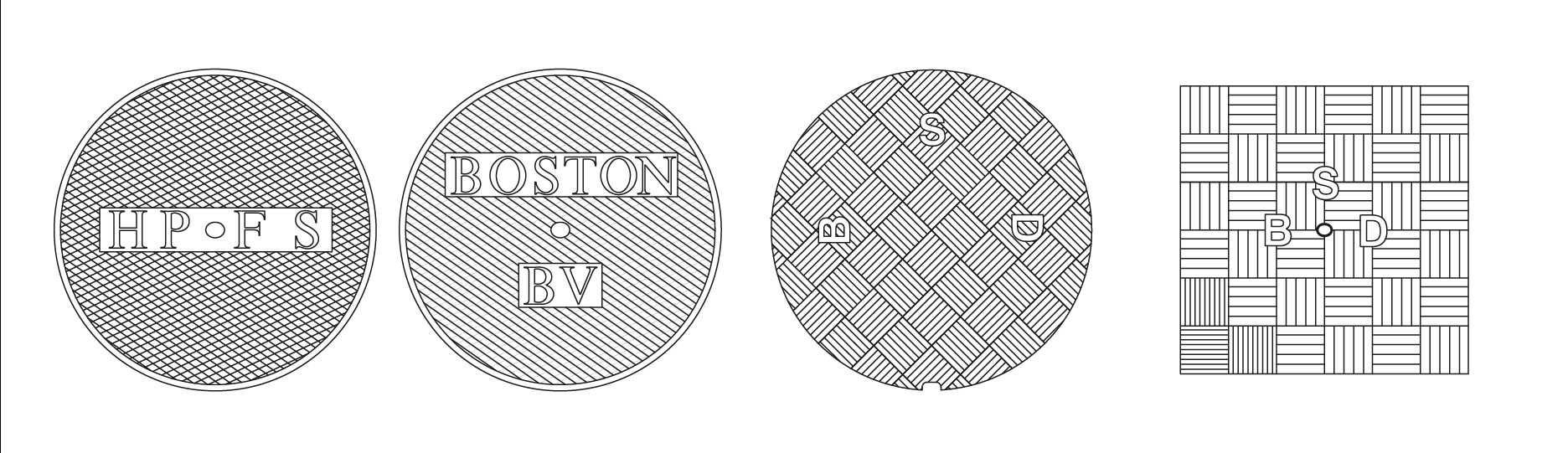

“Know Your Water” came out of an interest in the hidden infrastructure of the city. Cities have complicated networks of resources that lie beneath them and only through the occasional clue, such as a manhole cover, are we even aware of their existence. Water, electricity and gas all appear at the click of a switch as if by magic; their supporting infrastructure only questioned when there are problems. I was particularly interested in the water network of Boston due to the sheer size of its supporting infrastructure. Reservoirs and aqueducts are incredibly large interventions and Boston has one of the largest man made reservoirs in the world. How have these massive landscape interventions been so successfully removed from our consciousness?

The first half of the semester was devoted to demystifying the water network, understanding all of the pieces of the potable water system from collection to use with the ultimate goal of targeting issues within the system that need to be communicated to the public. Since people tend to be very proactive about pushing for improvements in visible infrastructure such as streets, I hoped that I could help encourage them to take an equal interest in their water infrastructure and push for improvements in the aging underground networks.

Through research and interviews I realized that most of the issues in the Boston area lie not within the potable water networks, but post-use in the sewers. For example, combined sewer/storm water overflow pipes are driving the design of our sewer systems and waste water treatment plants, causing major inefficiencies in the system except during large storm events. Additionally, due to old pipes, clean water is infiltrating into the sewers which, combined with a largely impervious surface, are lowering the ground water level causing historic wood pilings in buildings. However, the most essential piece of information I found was that the knowledge gap between the user and the water system is at a very basic level. Partially due to the abundance of rain in the region, clean water is majorly undervalued and many users don’t understand why they should conserve it or even pay for it.

Currently, the average person pays only 1 to 2 cents per gallon for tap water in the Boston metropolitan area. Considering that as our population grows water is only going to get scarcer and prices cannot remain so deeply subsidized indefinitely, the goal of the project shifted to address the education of the average user towards the larger infrastructural, resource and ecological requirements of water usage.

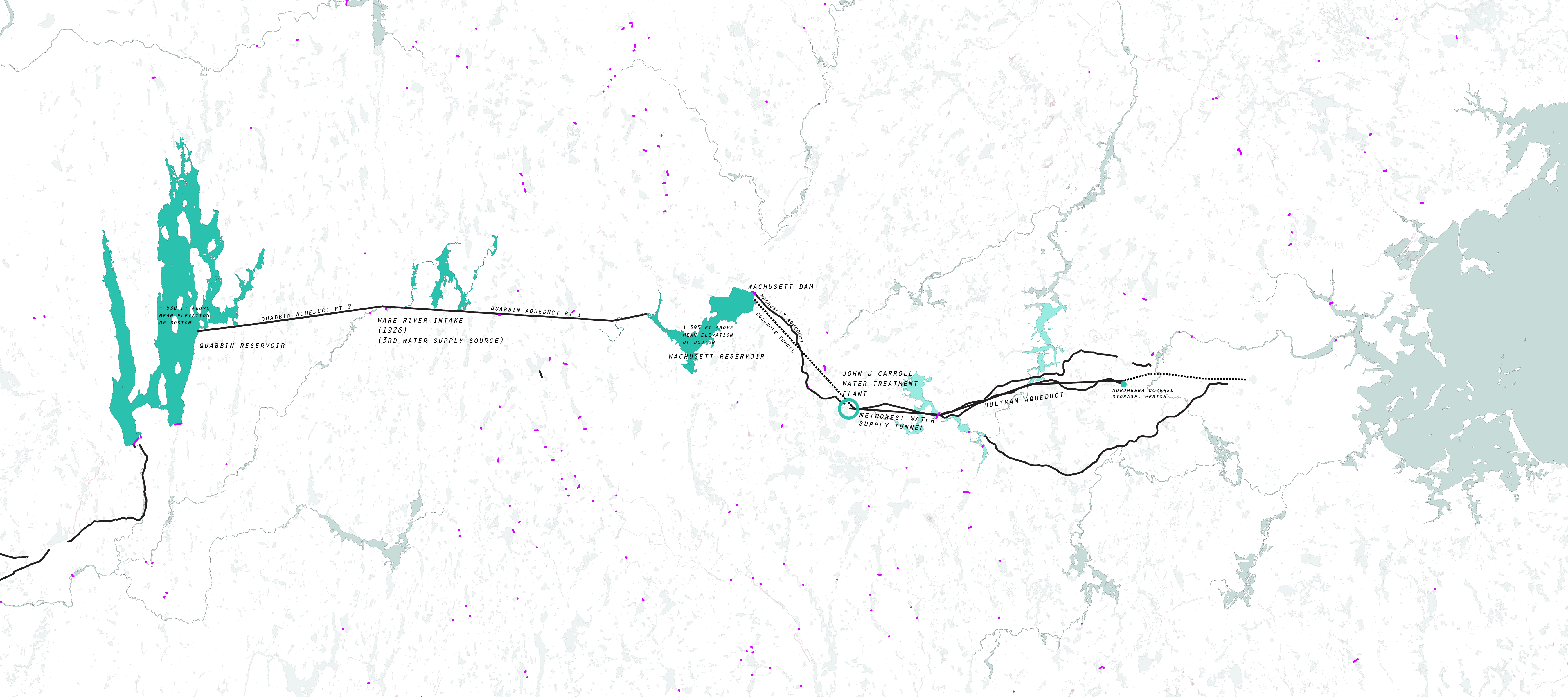

The infrastructural requirements to provide water to the entire Boston metropolitan area are obviously quite extensive. There are three water sources feeding the system: the Quabbin Reservoir, the Wachusett Reservoir, and the Ware River. Much of the land that drains into these sources, especially the Wachusett and Quabbin, is protected and came at the cost of displacement of multiple towns. Additionally, the water travels at least 80 miles from collection to ocean release in pipes that range from 4 inches 23 feet in diameter.

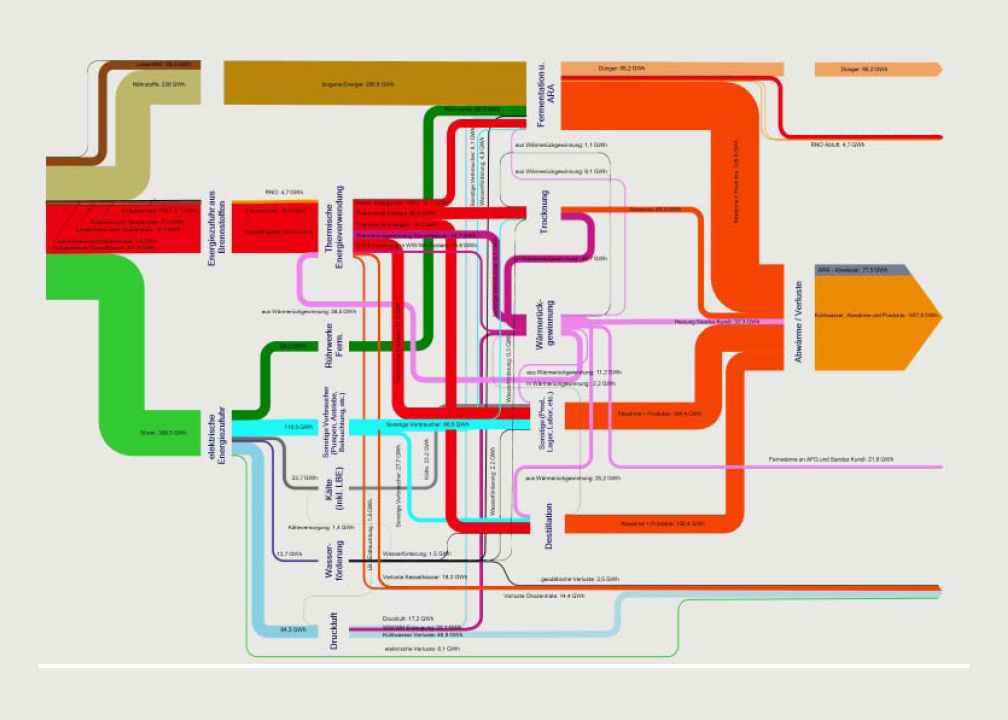

There are also many other resources required in this process. A huge amount of energy is necessary to pump and treat waste water and despite many efforts to use renewable resources as often as possible by the Massachusetts Water Resources Aurthority, 84% of the energy they use is still coming from power plants. There are also several chemicals that go into the water treatment process, disinfecting and altering the water composition.

Perhaps most importantly, the understanding that our water usage is part of a larger, connected system is crucial. Our use affects ecosystems on both sides of the chain, and if the awareness of where our water will go can be achieved, then perhaps we can start to make smarter choices about our usage and what we put down the drain.

“Know Your Water” is not just about the water system alone, but is also an exercise in effectively conveying information. Much of my research is available through various water authorities’ websites but is not presented in an easily accessible format. The process of water usage is complicated and systemic; the typical diagram is not effective at communicating these types of overlapping processes. Through a reiterative method, I used animation as a tool for experimentation in communication. The resulting short animation is hopefully not just explaining the process to users, but by presenting the information in a neutral way, is asking people to have an opinion about it. Working with the water resource authorities to make this film most effective, it would ideally be provided to users at the point of payment online. This animation is only the basic information, leaving many opportunities for the more specific sewer issues to be addressed in accompanying videos.

The carbon counters (in both physical and digital form) are meant to stimulate discussion about carbon emissions and climate change at the school of design. The impact that our buildings have on the environment is an issue that is often glossed over at the school of design as it is in most public discussions. If we want to address our concerns for the environment, issues of climate change need to be brought into our collective consciousness and that starts with raising awareness about own carbon footprint.

Climate change is an issue of global concern, with deep roots connected to everything from aging infrastructures to shortsighted policies and regulations. However climate change is also largely the result of behaviors caused by a lack of awareness about the impact our actions have on the environment. Every time we use our computers, turn on the air conditioning, or take a shower, we are releasing carbon into the atmosphere and contributing (in a small but nonetheless significant way) to global climate change. As a result of this general unawareness, people leave their lights on during the day, turn the air conditioning on high in the summer, and take hot showers longer than necessary – exacerbating the problem of global warming.

This semester began with an assumption that educating the public about the way our built environment works, specifically the way our built environment uses energy and contributes to the problem of global warming, has the potential to correct some of our more problematic behaviors. One component of education is finding ways to visualize the invisible yet ubiquitous energy infrastructure and how that infrastructure operates. The other is to visualize the real-time impact our buildings have on the environment, and in so doing affect the decisions we make regarding how we interact with the built world.

While there are undoubtedly many ways to communicate this information, the studio was an opportunity to experiment with an unfamiliar medium: animation. The first experiment involved an animation describing the movement of energy from the point of resource extraction to the point of consumption (the city of Boston). Since Boston, like many northeastern cities, creates most of its useable energy from burning natural gas, the animation begins in the Mississippi Delta where most of the nation’s natural gas is processed before it travels via one of several large pipelines to the electric generation facility. The fact that Boston relies heavily on natural gas for its electric generation is an important point because it enables one to calculate the amount of carbon created per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated.

This first animation was an introduction to new tools, and new techniques of representation. While it was an informative exercise, it failed to communicate the urgency of reducing our collective energy footprint. The description of resource movement from source to sink was ultimately too abstract and removed from the everyday behaviors of ordinary citizens. Using the lessons learned from this first iteration, the second animation used data collected from actual buildings to concretize what was formerly too abstract.

Even with the complexities involved in the processes of energy generation and transmission (deregulated markets, interconnected power grids…etc.) collecting and animating information about how specific buildings or groups of individuals use energy is decidedly more difficult. In order to streamline the research, Gund Hall served as a test kitchen because of their psuedo open data portal to energy monitoring systems. Real-time data on everything from lighting loads to steam use is continuously collected, packaged, and then emailed as a text file once per day. Using this information, the numbers in the animation are presented in traditional terms, such as a Kilowatt-Hours for electricity used for lighting and therms for heating, as well as comparative figures such as number of houses powered per year. For example, the amount of energy used to light Gund Hall is equal to the amount of energy it would take to power 208 medium sized houses. The numbers and figures are also presented in relation to other buildings on the Harvard campus as a way to accentuate the point that Gund uses more energy per square foot than almost any other building in the area except the Science Center (and most of this energy goes toward unnecessarily lighting the building during all hours of the day).

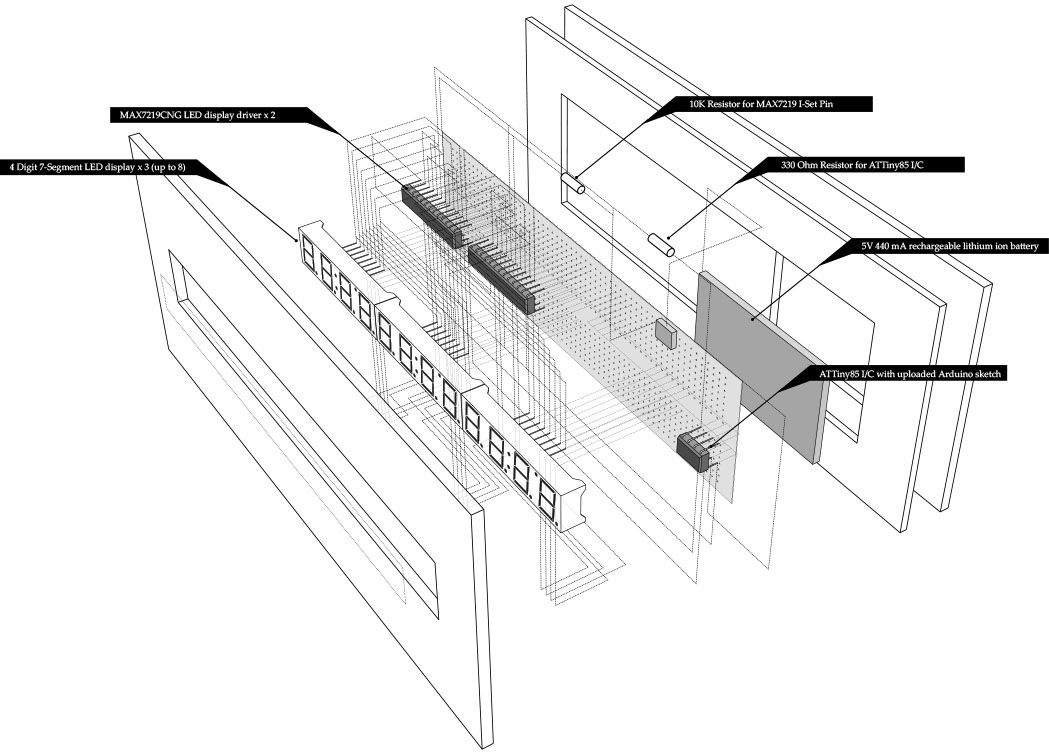

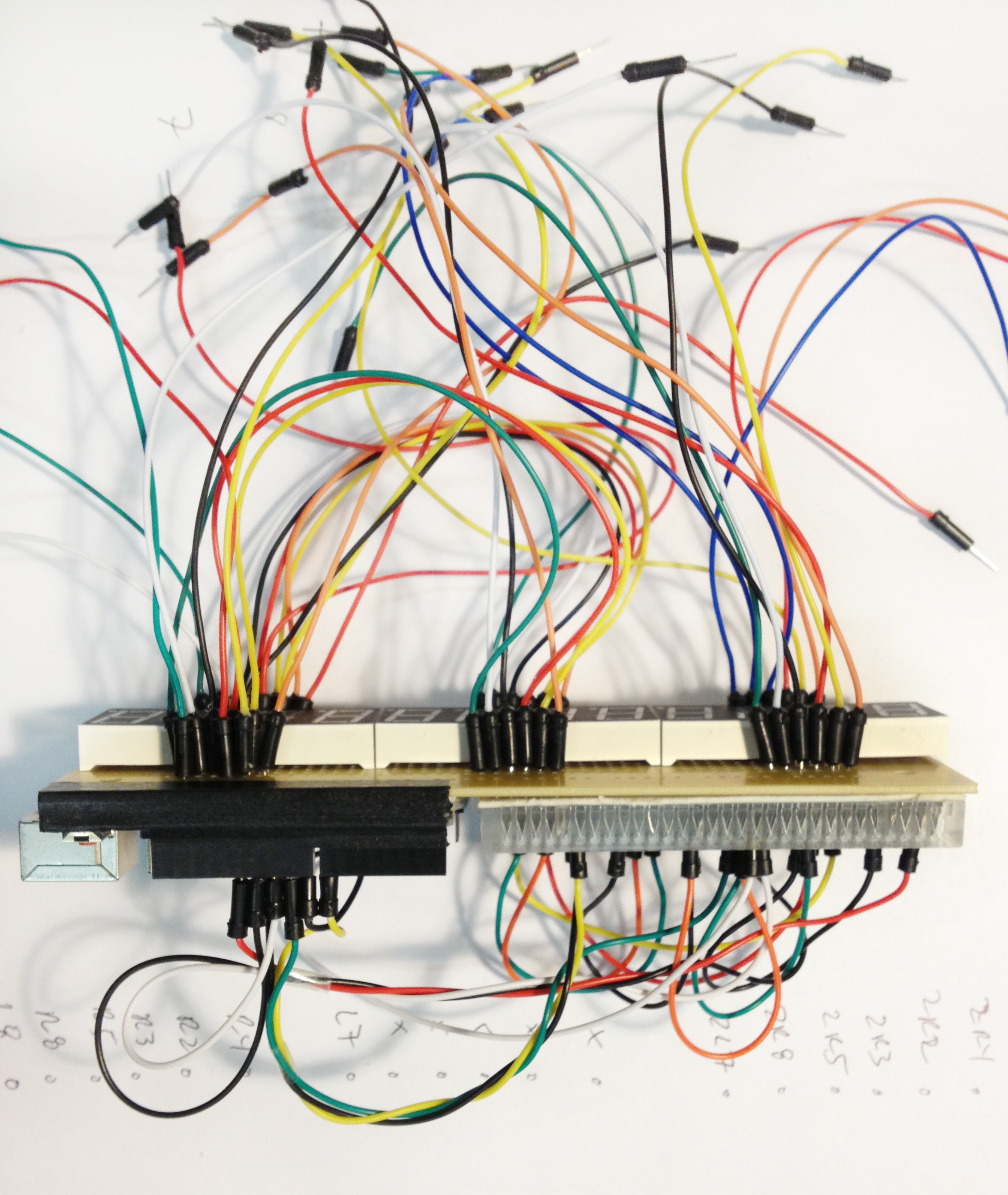

This animation played in the Chauhaus alongside a device that reads the (almost) real-time carbon emissions of Gund Hall. Although the output from this carbon counter is a simple number, the device was designed as an object of intrigue that people could walk up to and investigate – a dynamic and slightly more interactive type of informative poster.

These types of displays are particularly important for the design school, since we as designers are rarely confronted with the reality of how our creations impact the environment. Buildings account for almost half of all carbon emissions in the United States, and designers have a responsibility to create an efficient and responsible built environment. If an awareness of energy use becomes part of our consciousness as designers, and if we are constantly reminded of the ways in which our creations use energy, we are more likely to design and create a better built environment for the future.

The biggest challenge to reducing our collective energy footprint is visualizing what is normally unseen and forgotten, namely the energy we use everyday. Of course, even if our energy use is rendered as a number, or a graphic, it’s a bit too abstract to actually change our behavior. My initial experiments with this idea led to the development of the carbon counter that is currently displaying the carbon output of the GSD in the Chauhaus. The idea was that people would come up to this object of intrigue, snap a picture of the QR code, and be led to the Architecture 2030 Challenge website (which challenges architects and urban designers to realize net zero projects by t he year 2030). Not surprisingly, this device is pretty hard to miss, so I’m currently trying to think of an installation that will attract more attention to the actual flows of energy at the GSD. The installation is going to be coupled with a brief animation that describes all the ways that the GSD is using energy, and how to improve our collective performance.

Currently, I’m working on the back end of the system to get energy information in real time from individual plug loads. I received a plug monitor that runs the open-source protocol Zigbee that will interface with an Xbee adapter that I already have hooked up to an Arduino. The challenge now is to make the two devices communicate with each other, and then design a system that will turn this information into a visual and physical spectacle.

Bostonians, through their water usage, are one part of an extensive, connected system. The delivery of water to and from your home comprises of more resources than water alone and results in large scale infrastructural interventions that shape our landscape and impacts ecosystems on both sides of the chain. Through exploring methods of communicating these concepts, I hope provide a tool that educates users, encouraging them to reduce water usage and a have a better awareness of their environmental impacts.

Unfortunately, I’ve spent the last week out of the country so progress has been slow. However, I’ve managed to narrow down my research interest toward exploring ways to visualize and understand urban energy flows in and around Boston. At my desk-crit before I left, we discussed possibly creating a video or other type of visualization as part of an educational curriculum about energy conservation. Since the first step toward attacking an issue such as energy conservation is understanding the problem, I think a type of “Public Service Announcement” that makes people aware of how energy is distributed throughout Boston is a good start.

Toward this end, I’ve managed to arrange a couple of meetings this week with the office of sustainability at Harvard to get a grasp on how the university’s grid interfaces with NSTAR and other regional energy providers. They may also have some good ideas about how to kick-start initiatives aimed at conservation in an educational setting. I’d also like to talk to people at the School of Education at Harvard, and at some public schools in the area (one of my professors suggested I contact the people at the Cambridge mayor’s office for this) about what initiatives exist in terms of sustainability in the classroom.

On a somewhat related note, this was a quick concept collage that I came up with before I took off – the idea would be that kids could participate compete in program to monitor their energy use at home as part of a more comprehensive curriculum. I haven’t totally abandoned this idea, and I think I could roll it in with my other ideas to create a more holistic approach to this idea of understanding urban energy flows.

My work is focusing on explaining through mapping the paths and cataloging the infrastructure of Boston area potable water. This includes a mapping of water sources and guiding people through its paths while recognizing the extents of power and infrastructure required to make water easily accessible.

The aim is to help make people more aware of where their water comes from, the resources involved and the politics behind it in order to help them make more informed decisions and be more responsible with their water usage.

I have been speaking with other researchers who work in the field as well as people involved in the water world of Boston. Some things I have coming up coming this week, a meeting with some important people at the Metropolitan Water Resource Authority, a visit to Deer Island Treatment Plant and the MWRA museum.

I’m proposing to link the idea of understanding energy infrastructures with public education. I think there is a way to encourage sustainable behavior insofar as it relates to energy conservation by engaging a network of young students in Boston. The first step is to visualize the vast amount of information that exists about our energy infrastructure, and then create a system whereby students can interact with that infrastructure via a web or mobile interface to a social network. Without going into too much detail, I think it’s possible to combine educational programs with incentives to conserve and/or responsibly use energy (in all its forms). I am really inspired by the Natural Fuse project by Usman Haque, and I’m wondering how that system might be scaled up.

Think Big:

How can we encourage people to understand, appreciate, and sustain our urban energy infrastructure. Is it possible to develop a system that teaches people to conserve energy, on a scale large enough to make a significant contribution to offsetting our collective carbon footprint?

Start Small:

The first step is simply to understand how energy is created, distributed, and consumed in the city of Boston. In order to approach the complexity of the energy infrastructure that exists in this city, I propose to develop an energy monitoring and visualization system for a select number of households, to get a sense of how a typical Bostonian uses energy in real-time. The next step is to connect this system to social networking sites (Facebook/Twitter) and open the platform up to students in the area. The ultimate goal is to incentivize energy conservation by engaging a large network of students who can keep each other accountable in terms of their energy use.

Act Now:

Currently refining the ideas of the proposal, and trying to think how this system might be different from energy conservation programs that have failed in the past. What would be the most effective way to visualize the information at hand, and how will I engage the community to garner interest in the project?

1 2 3 Next »