Networked Urbanism

design thinking initiatives for a better urban life

apps awareness bahrain bike climate culture Death design digital donations economy education energy extreme Extreme climate funerals georeference GSD Harvard interaction Krystelle mapping market middle east mobility Network networkedurbanism nurra nurraempathy placemaking Public public space resources Responsivedesign social social market Space time time management ucjc visitor void waste water Ziyi

waste

Understanding waste as an inseparable part of the lifecycle of materials and the ‘metabolism’ of cities, and approach it consequently. How is waste understood and managed? Can we make this process more ‘visible’ for the general public? Can waste be understood as a resource?

Aeon is a time-balancing tool for a new era. Holistic, visually inspiring, and privileging flexibility over linearity, Aeon innovatively combines the calendar and to-do list, and helps find time for the important things in life. With a basis in neuroscience, Aeon’s qualitative approach facilitates efficacy and integrates space for restorative moments.

Time. There never seems to be enough of it. Even as technology increases our efficiency, we continue rushing, often leading to imbalance and ineffectiveness in our lives. As we strive for productivity, we often underrate the critical role of rest to our cognitive and creative abilities. Multitasking has become the norm, diminishing our capacity to focus on one task at a time. Perhaps most of all, in the rush to complete everything on our plate, we often put off the important things in life. Combined, these imbalances lead to wasted time in our lives.

Time wasted includes what we do with our time and how we do it. But it also includes how we look at it. Our approach to time as a society is indicative of how we perceive it. Our perception and approach translate not only to our relative effectiveness in how we use time but also to our sense of time, such as a feeling of satisfaction and wholeness, or lack thereof. Aeon is both a reaction and answer to modern civilization’s perception of time and deeply embedded roots in a mechanized approach. It is born out of both the frustration of time wasted as well as the celebration of time itself.

Aeon was created to be a time balancing tool for a new era. (more…)

Cambridge, is home to numerous world-class universities including Harvard and MIT and over 105,000 residents that can be broken apart into three distinct groups, professionals, a strong working class, and the largest segment with over 40%, the students. More so, the governing bodies including the city and the universities are plagued with misaligned interests exposed through their resource allocation and differentiation of waste streams. Through quantitative and qualitative research including numerous interviews with a variety of stakeholders including the “city”, MIT, Harvard, and a survey that was completed by over 180 students and residents across the city. The research showed that the city has been left holding the “bag” at the end of the day. From each stakeholder’s perspective, waste was merely a byproduct of inconvenience. This spans each socioeconomic group that was contacted, and each institution, no matter how large or small—it is a matter of convenience.

This discovery, novel at best, led us to look for a moment to intervene within the system—one that is universal and would capitalize on current behaviors that could morph based upon the time of year, or the needs of the users. (more…)

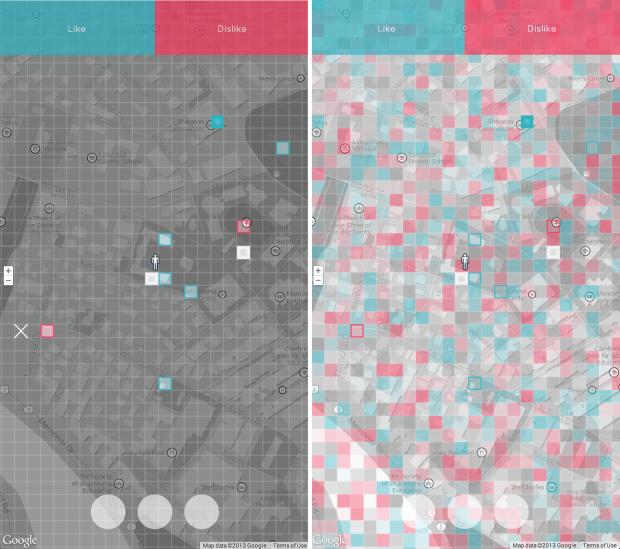

Pixel is a web-based application that enables the public to explore the city in entirely new ways. Through the collection and mapping of real-time public sentiment, Pixel also generates a layer of information that can provide planners and policy-makers with profound insights into how people experience the city.

Pixel has been in development for several months, and the process has drawn on the input of numerous researchers and experts in a variety of fields at the intersection of design, technology, and urbanism. (more…)

Temporary location of website: http://malayapapaya.com/bostongives/index.html

Each American throws away 1 million pounds of trash each year. Some of these items thrown away are still in good condition and can be used by someone else. Homeless adults, children, and families rely on nonprofit organizations, such as Red Cross and Cradles to Crayons, to collect and redistribute goods to them, the people who need it most. Some goods are shipped overseas to developing countries who rely on second-hand clothes for livelihoods and inexpensive clothing.

Currently, it is difficult to locate donation bins and centers. There is not one comprehensive source available to search for organizations with goods drop-off locations. People surveyed state they will often take the easy route. When they cannot quickly locate a place to donate their goods, they will throw them away.

When someone has located a donation bin, they might donate all of their goods to the single site, regardless of the type of goods the site will accept. This leads to unsolicited donations. Nonprofit organizations estimate 20% of goods donated are items they cannot use. It uses valuable resources, mainly volunteered hours, to sort the unsolicited goods and either find a new site to donate the goods to, or, in cases when resources cannot be spared, the goods are thrown away.

People surveyed state they would like to donate their goods rather than throw them away. Realizing the problem that it is difficult to find convenient donation bins and centers, Boston Gives, a web platform, was created to map collection sites and connect the community to local nonprofit organizations. It makes it easier for the general public to locate collection sites accepting donated goods.

The map is populated by the public and nonprofit organizations. Anyone can simply fill out a form from the website and a marker will be placed on the map. When a bin is no longer available, another form is available, and when completed, an “X” will appear on the marker, noting the collection bin or center is no longer there. Each marker provides information about the location, the hours collections can be made, and most importantly, the items that are accepted. By informing the donor which goods are accepted, fewer unsolicited donations will be made.

Boston Gives website also provides additional information about donating goods. For people who need to have their goods picked-up due to lack of access to transportation or the size of the good, such as furniture or vehicles, a list of organizations (with contact information) who will pick-up items is available. Organizations can also post drive events so the community is aware of goods that are needed most at the time. To reduce the amount of unsolicited goods, a list of “dos” and “don’ts” educate donors on the accepted condition of items.

Boston Gives can only be beneficial if the public is aware of its existence. To encourage people to spread the word of Boston Gives, the collection map can be shared on Facebook and Twitter by the click of a button. A link is also provided for other websites, such as government or organizations, to embed the map into their site.

Donating used goods conserves natural resources, lessens environmental impacts by reducing waste, and helps those less fortunate. It gives back to community and the planet.

Aquaplot uses discarded oyster shells from local restaurants to sustain oyster reefs and a re-establish a healthy harbor ecosystem by establishing a city-wide oyster gardening program that closes the oyster waste stream, restores native oyster reefs, improves local water quality, and reconnects the people of Boston with their waterfront.

We presented our proposal at our final review at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. During the review, we brought a bit of Boston’s Oyster Culture to the GSD with a live shucking demonstration and tasting session for our critics. This video was shown after our introduction to oysters and the potential use of their wasted shells.

Here’s our project video:

AQUAPLOT: an oyster garden proposal for Boston. from Kelly Murphy on Vimeo.

Aquaplot

Rethinking Boston’s Oyster Culture

To many people, Boston is synonymous with shellfish, especially oysters. Oysters have always been a cornerstone of the New England diet, and were once a mainstay in the Boston harbor. Oyster reefs were a crucial element of the underwater landscape that filtered our estuaries and maintained our harbor as a rich natural resource area. They not only clean water, but also act as shoreline buffers that dissipate wave energy. What’s more, they support critical fisheries by providing habitat for numerous fish and crustacean species. Oyster reefs, however, are now the most severely impacted marine habitat on Earth: over 85% have been lost globally.

In today’s context we hear a lot about oysters, whether it’s their ability to bolster coastlines in the face of climate change, their water filtration capabilities (the average adult oyster can filter 50 gallons of water per day), their potential for remediating eutrophic waters, or the food culture surrounding their consumption. There is, however, an important gap in this discourse: what about the waste associated with their consumption? What happens to oyster shells once they’ve been discarded?

Most people don’t recognize the magnitude of waste associated with discarded oyster shells once they’re consumed. In Massachusetts alone, 4.1 million pounds of oysters were harvested last year. Over 40 restaurants in Boston serve oysters, lending a distinctive identity to our city. Each restaurant generates around 20 pounds of oyster shell per day. Together, this totals over 300,000 pounds of oyster shell per year in Boston alone. Of these 40+ Boston restaurants, only 4 recycle their shells, meaning that 90% of shells are currently landfilled. Why? Because Boston doesn’t yet have a place for its shells.

How do you use discarded shells to sustain oyster reefs and a re-establish a healthy harbor ecosystem? By establishing a city-wide oyster gardening program that can close the gap in the oyster waste stream by creating demand for discarded shells. Oyster gardening can simultaneously restore native oyster reefs, improve local water quality, and reconnect the people of Boston with their waterfront. There are a number of successful precedents for oyster gardening programs around the region. There is no reason why Boston shouldn’t be at the forefront of oyster gardening given its rich heritage.

Oysters are relevant to the economy of the city and represent a local heritage that people are extremely proud of. While Boston is known for its shellfish, however, it is not performing well on the shell recycling front. Within this broken cycle lies an opportunity for the Boston to address two key problems: wasted shells and oyster reef decline. While there are numerous productive uses for discarded oyster shell, the best use by far is as reef substrate to grow juvenile oysters. The link between the two problems presents an exciting opportunity to propose a better system.

The waters of the Boston Harbor are currently closed to shell fishing due to the risk of oysters being harvested illegally in polluted waters. However, nursery areas for shellfish seeding projects are permitted if they are transplanted to approved waters. Over the last three years, the Massachusetts Oyster Project has proven that oysters can survive in Boston Harbor. In just a few years, oyster gardeners could use discarded restaurant shells to grow thousands of oysters in the Boston Harbor and re-stock endangered reefs in the region.

The benefits of oyster gardening are manifold, and span environmental, economic, and social realms. Oyster gardening connects the waste source to the solution, revives Boston’s local heritage, reconnects people with their waterfront, and brings life back to Boston Harbor.

Here’s our presentation:

AQUAPLOT | Final Presentation by networkedurbanism

Aquaplot by Jenny Corlett + Kelly Murphy

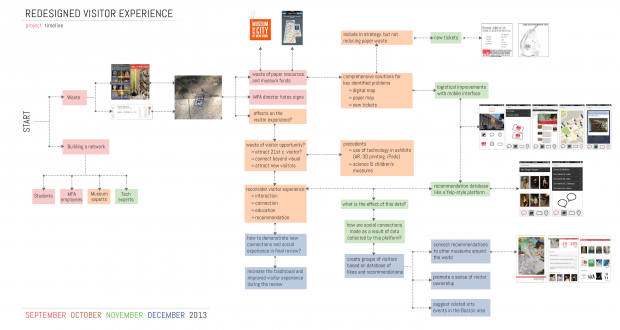

Redesigned Visitor Experience aims to enhance visitor-to-object connections and create visitor-to-visitor experiences within an art museum. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which welcomes nearly 1.5M visitors annually, was the museum of interest throughout this process.

Initially, the focus was on the waste of physical resources of the museum: the paper used to produce thousands of maps and millions of tickets annually, and the funds required to print this collateral. An app to support logistical improvements, including a digital map, access to the museum’s web catalog, and the opportunity to buy tickets from a smartphone, was the first stage of solutions. Many lower-level members of the museum staff were incredibly helpful in providing initial feedback about the current visitor and wayfinding experience. After several dead-ends and false starts, it was necessary to explore another approach to the museum and its relationship with waste. Though helpful, this type of app was not particularly innovative, and led to a consideration of a waste of opportunity in the form of visitor experience. How can museums encourage connection, education, and interaction, beyond design of the exhibitions themselves? How can data analysis play a role in creating new networks that continue to develop outside of a museum?

In contrast to a science museum or a children’s museum, art museums tend to be more conservative and traditional. Artifacts and precious objects are stored behind glass for safety, with only small plaques of information available. Additional Information is relayed primarily visually and unilaterally: directly between the visitor and object. There is little interaction between visitors, unless they arrived in groups together. Visitors can view the same objects without acknowledgement of a relationship between objects and visitors. Arguably, the quiet of museums allows for enjoyment of the arts, and while this is true there is still a sense that another layer of understanding and connection could exist.

Imagine a digital platform that could promote and support these additional connections, while collecting valuable data for the MFA. For example, a visitor sees a painting that she likes. She simply clicks on its image in the RVEx mobile application, and it will pull up some basic information about the work, including artist, title, and date. The images and the details about all of the museum’s works will be populated by the museum’s own directories of its collections.

She can then tap to access the section for visitor participation. She can view other visitor’s comments and suggestions for the painting, and how many people “liked” and people have seen the painting so far. She has the option to leave a comment, or scroll through previous time-stamped comments. This page operates similarly as if the work had a Facebook profile. The app provides visitors with related objects that they can see in the MFA, if they particularly liked this painting.

A visitor profile allows you to save works that you like to a personal gallery, as well as your recent activity. The visitor can remember the name of a work she loved, share it with others, or just keep it on hand for a return trip to the museum. This app can function as digital pocket gallery, and your favorite art can quite literally be at your fingertips. A visitor can also access groups, settings, and recommendations for international museums, local events, and other pieces of art. This app can be used daily by an art lover, or as a digital way to collect a souvenir when on vacation.

What takes the platform beyond a Yelp or Foursquare review-based platform, this app includes groups. The groups are created based on an analysis of data of a visitor’s activities: what they’ve liked and seen. The museum and the art serves as the starting point for creating these kinds of connections that can eventually flourish beyond the physical space. Perhaps most interestingly, the app intends to provide “group based recommendations.” Again on an analysis of data, suggestions are generated for art found in the MFA that may interest members. Next are recommendations for local events, which pushes the network outside of the confines of museum. Finally, the platform suggests international museums that may be of interest. Eventually, these could have their own similar platforms and catalogs, so you can view and save art, and connect with other members from around the world.

Note about the copyright for images of paintings, sculptures, etc. used in frames from the above presentations: I do not own the images and they are the property of the MFA, from www.mfa.org.

MYPS is personalized cloud to ground cartography that reshapes both how we compose our farewells and how we receive the farewells of others.

A P.S. is an afterthought – an easily appended message that crosses our mind after we think we have said all we mean to say. Yet the postscript also contains our final words, which are actually quite powerful. When combined with the power of place in the development of memories, these afterthoughts can create meaningful journeys for our loved ones to revisit after we are gone.

MYPS uses the GPS capabilities of mobile devices in combination with familiar media sharing formats to facilitate the process of recording our shared memories so our loved ones may literally revisit them after our passing.

The following video is a preview of my final review “experience”. It shows how MYPS could tie together three generations of memories. When my Mom came to see me in Boston, we visited the places my grandpa remembered from his own time living here during World War II. After her passing, I will be able to revisit our route to see the memories she left behind.

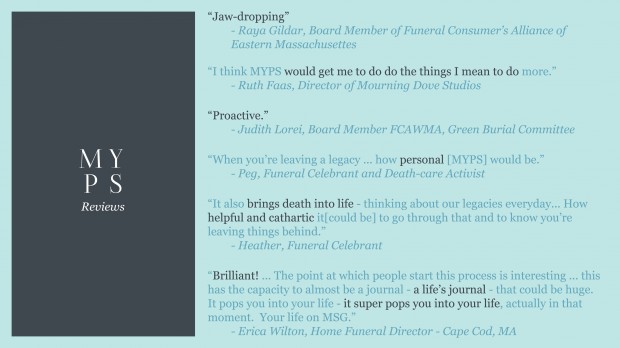

I was invited to participate in a networking event by Ruth Faas, my main contact in Boston’s death-care industry, on December 8th in Arlington, MA. Attendees included board members of both the Eastern and Western Massachusetts Funeral Consumer’s Alliances, Grief Therapists, Artists, Funeral Celebrants and Funeral Directors. Here’s what they had to say about MYPS…

In the middle of November, we were asked to create a proposal for the final review “performance” for former Loeb Fellow Jim Lasko.

1 2 3 … 7 Next »