Networked Urbanism

design thinking initiatives for a better urban life

apps awareness bahrain bike climate culture Death design digital donations economy education energy extreme Extreme climate funerals georeference GSD Harvard interaction Krystelle mapping market middle east mobility Network networkedurbanism nurra nurraempathy placemaking Public public space resources Responsivedesign social social market Space time time management ucjc visitor void waste water Ziyi

“We all come to know each other by asking for accounts, by giving accounts, and by believing or disbelieving stories about each other’s pasts and identities”

Paul Connerton, How Societies Remember

This project began with a question about how people connect to places. As our lives become ever more transient, the stable relationships with place that have defined communities for generations are evaporating. Many of us now inhabit places whose history we have no understanding of, no personal connection to. What happens to the identity of a place when its residents have no memory of it?

Boston has a strong tradition of collecting oral histories of place. Organizations like the Cambridge Historical Commission, South End Historical Society, and other community groups have archived personal stories about places in their neighborhoods, maintaining a link between the physical fabric and the lives it contained. But how many people know about these archives? How many of the current residents can point to a family members story contained therein? Do these archives invite their viewers to contribute their own stories? Do they encourage us to explore our environment, to connect the physical artifacts with the stories they hold?

Changes in our technological environment have made it easier than ever for us to connect to each other, to share the details of our lives (however banal), and to map with pinpoint precision any number of events. Don’t these new tools offer an opportunity to bring the archive of personal histories out of the library, onto the street corners where they took place? Rather than simply absorbing our neighbor’s stories, shouldn’t interactive media allow us to be both speaker and listener? To enter a dialogue with the history of place? To have our own place within that history?

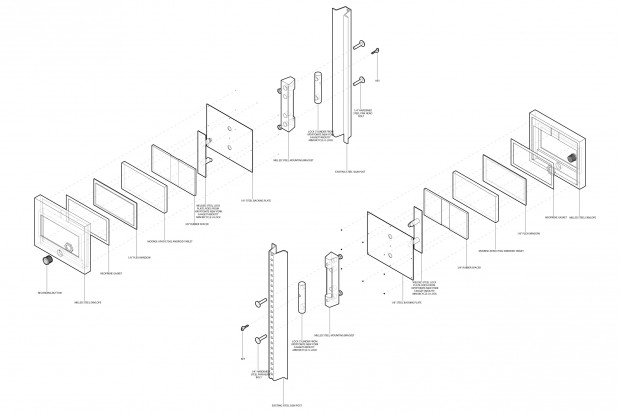

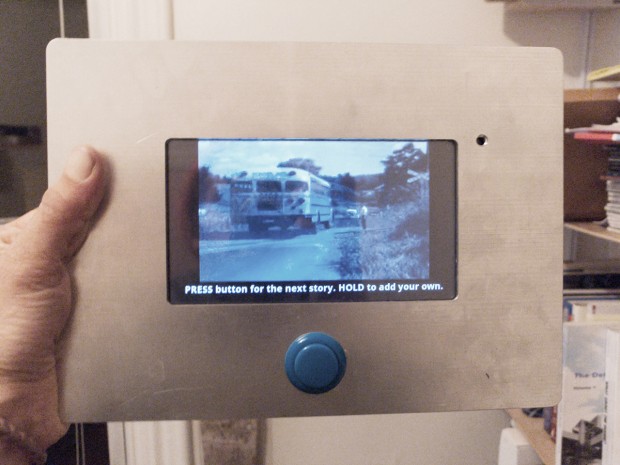

To explore these possibilities, I sought a way to connect personal stories about place with their actual settings. The result was a device that mounts to the nearly ubiquitous street sign. As a person passes by, their curiosity is aroused by a foreign looking object, inviting them to see what happens when the push the brightly colored button. When she does, she is treated to a highly personal “seed” story, one that takes place on the very ground upon which she stands. “This is where I waited for the bus to school every morning 11 years of my life. Here I made some of my best friends. I remember the time when …” The viewer is then invited to push the button again, to record their own story about that place, or to react to the story just played. Over the term of their deployment, the device accrues more and more layers of personal narrative attached to the place.

As I worked on the design, I began to seek content for the device. After meeting with several people who had worked to build oral history archives, I met a group of young high school students who were tackling some of the very same questions as myself. As a part of a program called YouthStream at Cambridge, the students were learning the art of storytelling, and exploring ways that new visual media allowed them to share their stories. What made the collaboration even more fruitful was that these students were specifically focusing on stories that connected their personal lives with public places: each student picked a street corner in Cambridge that held some personal memory, and developed techniques for conveying that story both visually and aurally. By exploring what was happening outside of the walls of my school, I was able to find others to work with, which helped me explore my ideas, and allowed me to help them reach a broader audience.

The collaboration resulted in a trial run in January of 2011, which was a moderate success. I installed the device at a bus stop in Union Square, with a seed story about a child’s experience of maturation, set at a bus stop and on the bus. The story was funny, touching, poignant, and personal. The device succeeded in attracting listeners, and even recorded a few reactions. Though it didn’t work as well as I had hoped, it has led to a new collaboration with another research group at called metaLab. While the content has changed in the new exploration, the core ideas of connecting people to place through tangible, interactive media remains the focus. What is particularly exciting is that the problem we are working on requires us to explore both the tangible and intangible aspects of media: the physical presence of the object must grab a person’s attention, inspire his curiosity, and invite an interaction, while the intangible content must be satisfying, bring joy or a new understanding, and make us think about the world in a way we hadn’t before.