Networked Urbanism

design thinking initiatives for a better urban life

apps awareness bahrain bike climate culture Death design digital donations economy education energy extreme Extreme climate funerals georeference GSD Harvard interaction Krystelle mapping market middle east mobility Network networkedurbanism nurra nurraempathy placemaking Public public space resources Responsivedesign social social market Space time time management ucjc visitor void waste water Ziyi

City of Snowmen was a project about exploration, production, and memory in the context of winter in Boston, Massachusetts. Participants were encouraged to build snowmen in public spaces and then photograph and map them to a website. The project aspired to provide users with a map of their city’s snowmen, a guide for seeing the built environment through a new frame. Participants were few but enthusiastic. With strong and consistent energy directed towards outreach and communication I believe a City of Snowmen project could flourish in a snowy region, becoming a public activity requiring only minimal investment on the part of several organizers.

I grew up about six miles from downtown Boston, and compared to most of my classmates at the Harvard Graduate School of Design I knew the city with a degree of intimacy and awareness. Boston is known for its colleges and universities, but experience taught me that relatively few students made efforts to discover the area’s many neighborhoods. Fields Corner, Roslindale Square, and Fort Hill are, to me, delightfully different from more trafficked neighborhoods, such as Allston, the Back Bay, and Harvard Square. Interviews with Boston natives, however, indicated that this unfamiliarity with other neighborhoods was not limited to students from outside the state. I found that native residents were very loyal to their own neighborhoods, but they saw few reasons to venture beyond their comfort zones. This led me to wonder how I could foster in both permanent and transient Bostonians a sense of curiosity and mystery around places so close yet unknown. What would it take to excite someone enough to leave their apartment in Brighton and spend a leisurely hour in South Boston?

The endeavor underwent three iterations. At a first stage, I envisioned using video cameras to project in a public space lives scenes of another public space in Boston. Thus, a person walking down Center Street in Jamaica Plain would see a live street scene of Dorchester Avenue, at the other end of the city. The idea of this installation seemed too targeted, however, and I hoped to develop an idea that would not involve complicated coordination or technical curation.

I next focused my attention on Fort Hill, a quiet neighborhood in Roxbury, Boston. Walking around Fort Hill I felt that it was a neighborhood visitors would find relaxing and unexpected. I explored the use of maps and cairns as tools for visitors walking around the neighborhood. Cairns are man-made piles of stones typically found on mountain tops above the tree line. Hikers use the cairns to mark their path, and one may add stones to cairns while following the delineated route. I liked that cairns granted a tool to participants to more directly add something to their environment. A cairn reflects a collective authorship over a path through space, and it hints at an anonymous human presence. In some ways these feeling reflect how we build cities over time.

A year prior I ate a stale piece of butterscotch candy at a friend’s apartment and discovered Relational Aesthetics. My friend had saved the candy years before after visiting an installation by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Placebo – Landscape – for Roni) (1993). The installation was hundreds of gold-wrapped candies carpeting a gallery floor, and visitors were encouraged to take the candy away. Relational Aesthetics is a term coined by art critic Nicolas Bourriaud in his 1998 book on relational art, and it proved a useful concept for broadening my understanding of how people may interact with installations. I was also inspired by Rirkrit Tiravanija‘s seeing art in serving food to visitors in a gallery. Loosely, however, I hoped to appropriate these experiences and apply them to a process of construction by the participant.

People generally speak of winter in Boston with annoyance and dread. The city receives on average over 40 inches of snow a year, and this fact makes everyday walking and driving a challenge. At the same time, a snowfall in Boston brings strangers together. Bostonians are noted, amongst Americans, for keeping private, reserved dispositions (living in Los Angeles now, I am struck by the ‘friendly’ and talkative nature of strangers). Before a snowstorm, though, this changes. A sense of excitement and cooperation takes hold, and shoppers, for instance, are apt to engage in hasty but supportive conversations with their cashiers at the supermarket. Snowfall is a collective experience rooted in the physical transformation of the city’s landscape that affects how strangers see one another.

Images of snowmen crept into my imagination as the winter approached, and I wondered how Boston would look if residents built snowmen on sidewalks, in parks, and in public squares—places visible to pedestrians. Snowmen are nostalgic installations that anyone can construct, and though they generally are limited to traditional forms, the sculptor has broad creative license. The action of building creates an important element: the sculptor produces his or her temporary mark on the space. Unlike taking candy from a Felix Gonzalez-Torres installation, however, the snowman-builder is adding to the space rather than consuming it. It grants the Bostonian an opportunity to play city-builder.

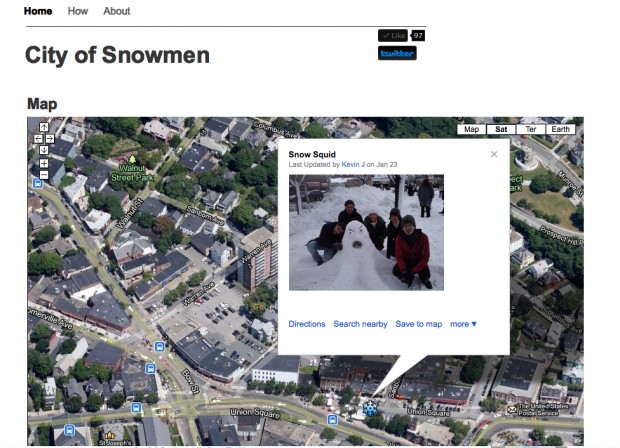

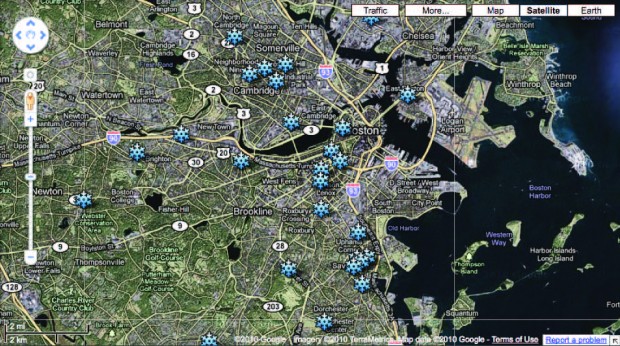

City of Snowmen, then, became a way for organizing this simple creative energy across Boston. Using Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, and Posterous, I attempted to draw attention to the City of Snowmen website. Participants were encouraged to build snowmen in public spaces, take a photograph, and email that photograph to our site along with the snowman’s address. The photo were tagged to an embedded map on the front page of the site, and visitors could click on snowflake icons to see images of snowmen in spaces across Boston.

The project aspired to reveal to Bostonians, through snowmen, neighborhoods they never would visit otherwise. It also aimed to show participants that building something in a public space adds to the collective experience of urban space. A pedestrian passing a snowman on the sidewalk is reminded of childhood, impermanence, and fun. It illustrates the mark people (not just architects, engineers, and planners) have on the urban landscape.