Networked Urbanism

design thinking initiatives for a better urban life

apps awareness bahrain bike climate culture Death design digital donations economy education energy extreme Extreme climate funerals georeference GSD Harvard interaction Krystelle mapping market middle east mobility Network networkedurbanism nurra nurraempathy placemaking Public public space resources Responsivedesign social social market Space time time management ucjc visitor void waste water Ziyi

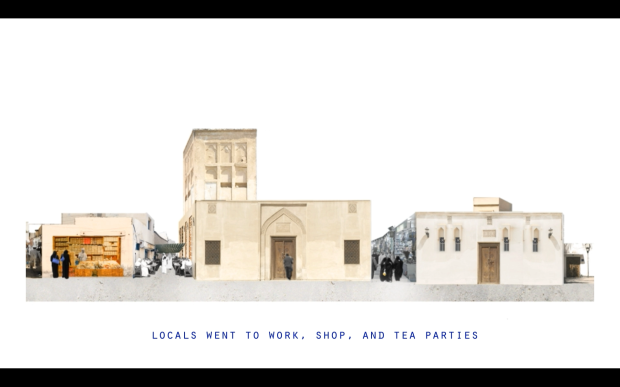

In Muharraq, the lack of public space is perpetuated by the extreme climatic conditions and the streetscape has evolved into an important form of public space for the citizens of Muharraq. When temperatures drop during the night, the streets transform into the social hub of the town with citizens who emerge from their homes and gather along stoops for conversation and people watching. However, the streets of Muharraq are mostly lit from lights within storefronts due to the lack of street lamps and as a result, these social activities mostly occur in the dark.

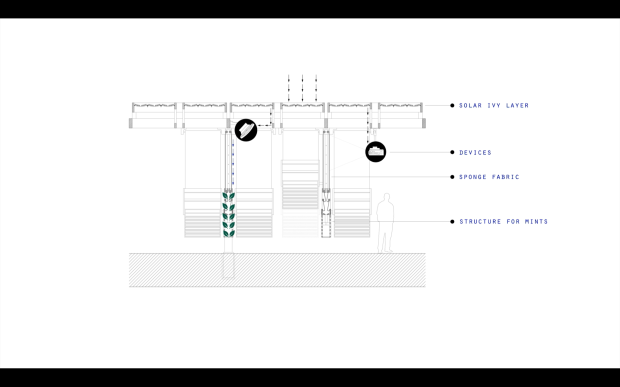

Breathing Streets is an urban intervention that changes the microclimate of the street and reinvents the streetscape. The urban intervention works as a system that shades, lights up, and cools down the streets.

The system begins with of a steel ring textile membrane structure placed in an open plaza within Muharraq. The ETFE textile provides a canvas for light projections during the night and filters diffused light during the daytime. Within the membrane, a mechanically pumped pneumatic vessel distributes cooler air to the adjacent streets through textile tubes that extend along the street. This membrane structure also functions as a heat chimney that allows hot air from the ground to escape into the urban canopy thereby cooling the space beneath the membrane.

In addition to these textile tubes, the streets are shaded with a multilayered textile canopy which diffuses the sunlight. This canopy can be customized with angled light wells that control the amount of direct sunlight depending on the season.

The use of thermal bimetals in combination with ETFE textile allows for the microclimate of the system to self-regulate. The textile tubes are fitted with bimetal nozzles that open and close in response to the temperature of the environment. Heat causes the metal to curve and open while cooler temperatures leave the material unaffected.

This system can be placed in plazas all throughout Muharraq to eventually create a network of cooler plazas and breathing streets. The cooler streets encourage pedestrian mobility around the historic city throughout the day by mitigating the harsh climatic conditions while the membranes in the plazas light up the city at night. The space beneath these membranes also serve as a new form of public space in the city wherein citizens and visitors alike can socialize with one another. Apart from the function of the space beneath the structural membranes, they also brighten up the city. The LED lights within the membrane use solar energy collected throughout the day and activate at night. Within the urban environment, they become large concentrated light sources that diffuse light through the dimly lit streets.

Breathing Streets is a system that generates an artificial breeze throughout Muharraq. A wind analysis in the historic city located plazas that experienced the least wind flow as possible locations for implementation. The simplicity of the system allows Breathing Streets to be implemented in one pilot location to test the effectiveness of the system. Over time, the system can spread to more locations around the city and eventually create a brighter and a cooler Muharraq.

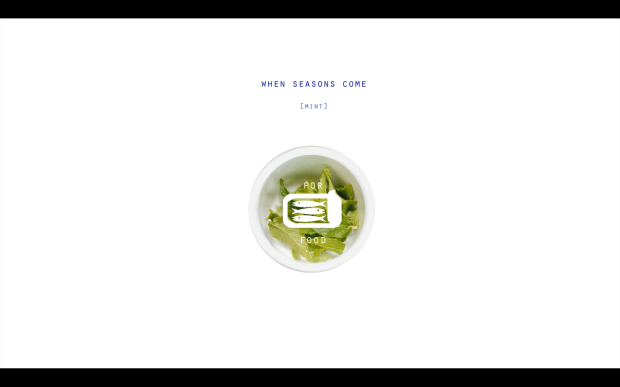

In Arabian, Bahrain is the dual form of bahr, meaning “two seas”. its rich marine resource has made it the top fishing spot in Gulf Area and a world-famous pearling site.

On land, its underground water system in the north, known as the aquifer, had offered a rare, arable oasis to grow trees, especially date palms. In fact, Bahrain is also known as the home of “a million palm trees”.

This might explain that, as an middle east country, only 25% of their fresh water comes from desalinization plants, while the rest majority from the aquifer.

However, as years passed by, this over exploitation boosted by the rapid oil-revenue development after the 1950s has caused both qualitative and quantitative deterioration of the underground water resource. For instance, sea water intrusion was to blame for the 79% increase of dissolved salt in underground water. And the increasing abstraction is bringing underground water level closer to the sea level annually. As a result, Bahrain’s tradition of palm planting, and its green north, has been withering with its trees.

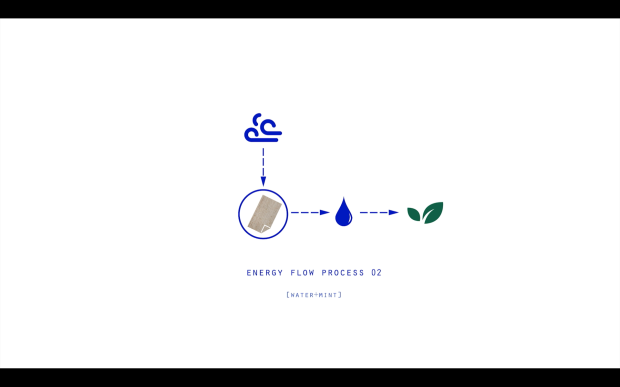

Our project aims to produce fresh water at low cost and then use it as a media to upgrade the local public space.

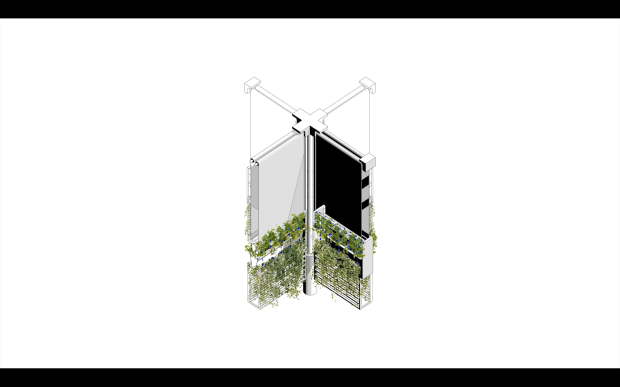

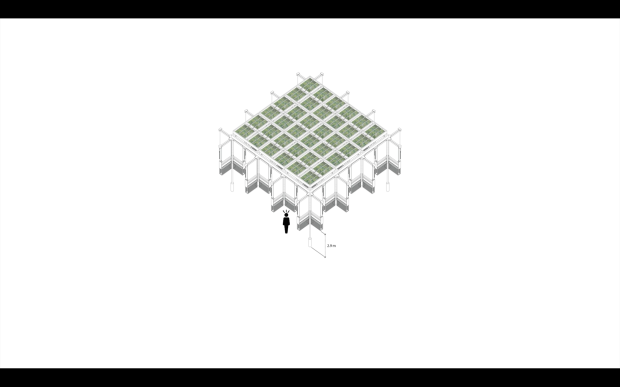

In Scheme 1, a modularized canopy will function as a distilling machine to produce fresh water. Each canopy unit has a reflective fabric to concentrate heat thus accelerate the process of sea water distilling. Then the fresh water flows down from the canopy to create water experience on the ground.

In Scheme 2, reverse osmosis technology is introduced to purify the domestic sewage collected from the neighborhood. The water is then used to irrigate the trees in the square nearby. We even have a relatively bigger version, a community park.

In Scheme 3 (final scheme), water treatment plants (like Typhas) are used to replace the Reverse Osmosis system in Scheme 2 to purify black water. The purified water will be used to irrigate the trees and grass on the roof. A staircase located in the atrium will lead people to the roof garden.

The core of this prototype is a well-planned circulation system. Black water is to be pumped into a bio-purification pond, where water plants eat almost all the organics and waste. Then the water filtered and pumped up to the pipes in the roof to irrigate the vegetation. At the same time, it also absorbs and takes away a large portion of the heat of direct sunlight.

Black water, this time, is considered to be a resource rather than waste, so we calculated the daily water consumption of the neighborhood and found that it is more than enough.

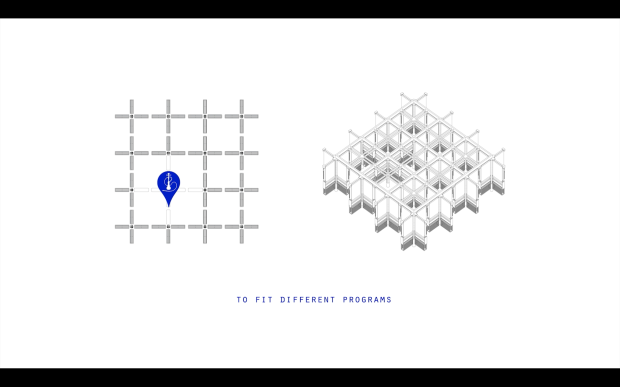

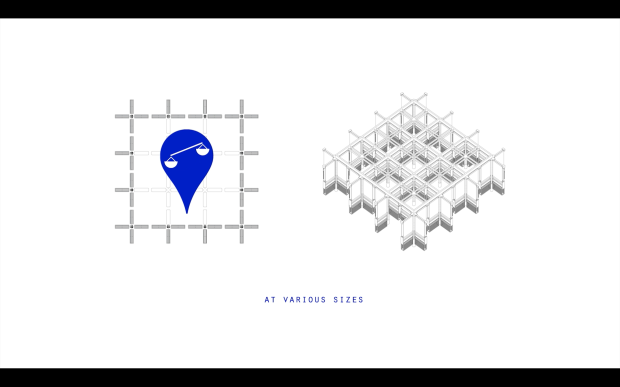

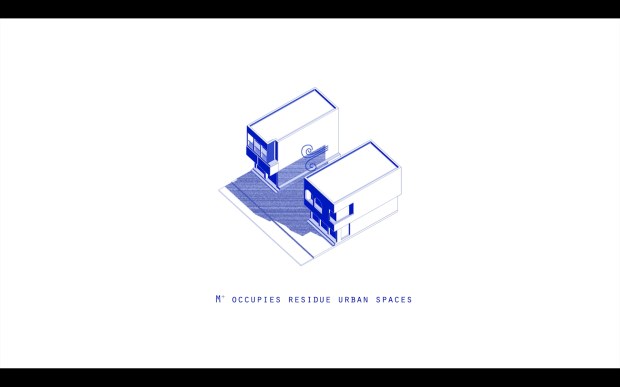

Each unit of our proposal will receive black water from its neighborhood and feed back with its public space on the ground level and most importantly an iconic green roof garden.

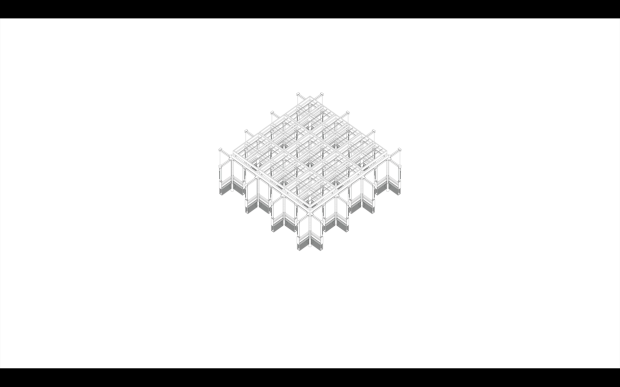

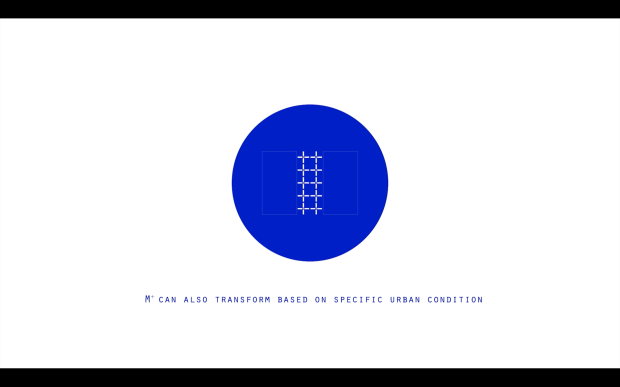

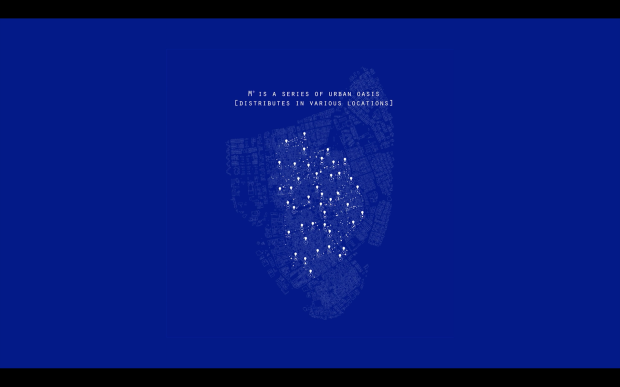

Zoom out, several units will form a micro urban oasis.

In a larger scale, we envision our proposal to be a network of green oases and a new layer of urban landscape.

This is the journey of our project.

This project proposes what a more robust mass transit system could do for Bahrain, it’s possibility as a systemic urban strategy and how public spaces can be utilized and enhanced in this system. It’s motivation is to provide greater accessibility and efficiency, but its goal is to create a cohesion between the many urban fragments. Our investigation of Muharraq led us to create an architecture that would looped and solidified these fragments. This continuum in space is a bridge that would enhance the daily lives and experiences of Bahrain. It would also reform many lost connections such as the relationship between the sea and city.

Bahrain is a small country located in the Persian Gulf. Bahrain means two seas and has a history that dates back to over 5000 years. Most of Bahrain’s urban areas are concentrated in the North, while desert covers the interior and south. Bahrain is an island and water plays a vital role in every aspects of its past and present. Land reclamation since the 1960s have changed the coastlines of Bahrain. Historic cores that once bordered the water are now landlocked.

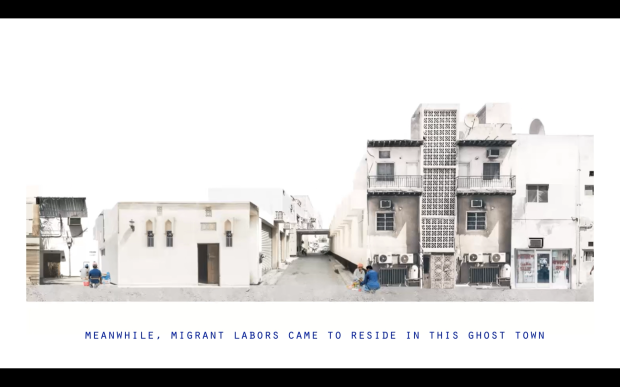

One of the major issue within Bahrain is the fragmentation of its cities. This transpired within the demographic and built environment of the country. Only 46 percent of the country is Bahraini. Migrant workers account for 77% of the workforce while also doing 98% of the low paying jobs. The average wait time for the bus in Bahrain is 40 minutes. Making it impossible to get around by public transportation. Bahrain will need a mass transit infrastructure 4 times larger than today to adequately service the country. Promoting accessibility and alternative mobility are the keys to Bahrain’s future.

We offer a vision of how an expanded mass transit infrastructure might change Bahrain, with lateral and vertical development that can sustain systemic growth and improve the urban context by making accessible public spaces and more vibrant communities. But the heart of our project connects Manama, the capital and Muharraq, the historic city into a necklace serviced by shuttles and a transport hub, and with stops at significant social, civic, and commercial areas. The architectural intervention that will link this connection is a bridge that spans from the historic city’s fabric, over a transit hub and highway, and into the sea.

This new bridge serves several purposes. It is made of a lightweight wood and steel construction that allows for it to span great distances. It uses textile to provide climatic comfort, and sustainable technologies to power itself. It starts at the old Muharraq’s suoq which is accessible from the Pearl Trail, a cultural route with several important historic landmarks, and establishes a covered public space that can be used throughout the day as the new fish market or a gathering place at night. The Muharraq suoq also marked the border of the water in the past, since the suoq were usually situated to meet the ships and their goods. This relationship of the old city to the water has been lost due to land reclamation. The bridge continues over a road and becomes an elevated transit hub for below. Further along the bridge, it crosses over a highway built in the 1960s that further isolate the historic city from the water. The bridge continues all the way into the water and ending with a floating barge that welcomes people to interact with the sea. The end point stitches back the old fabric of the city to the sea, while jumping over several obstacles to be functional as a pedestrian path, transit hub, and public space.

« Previous 1 2 3 4 5 6 … 38 Next »